At least Black Sabbath got to sell their own souls, and it was for rock and roll. We never even got that chance. A corporation I had never heard of this morning did it for us, and it was for AI training. So it goes. Informa, which owns major academic publisher Taylor & Francis (and Routledge), […]

Major academic publisher sold our souls to god of generative AI for a paltry 10 Million

Category Archives: Anthropology

If archaeologists can apply their skills to fighting fascism, so can other anthropologists… (& biologists, chemists, dentists, entomologists, geologists, harpists, lyricists, nudists, podiatrists, radiologists, zoologists…)

Futility of “Lest We Forget”

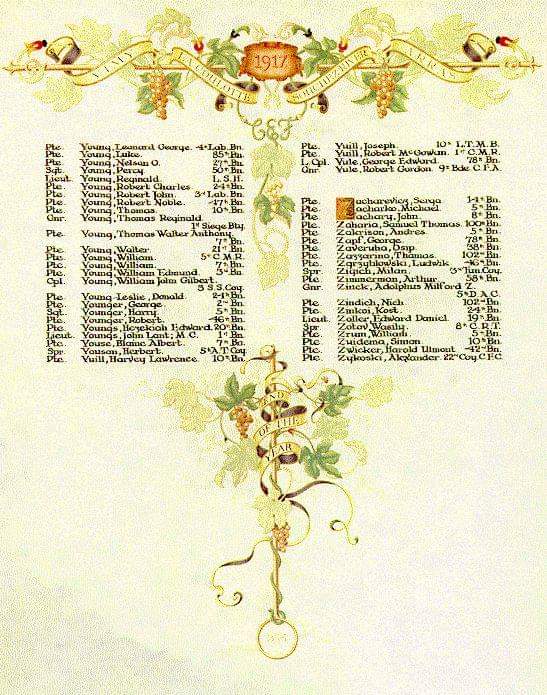

Remembering the great-uncle I never knew, Donald Young-Leslie, who enlisted Dec 30, 1914, served in the 24th Battalion Canadian Expeditionary Forces’ “Victoria Rifles” (Infantry, Québec Regiment) and was killed May 18, 1917 “in the trenches north of Fresnoy”.

Donald died one month after his, and his twin brother Norman’s, 23th birthday, and a bit more than a month after the Battle of Vimy Ridge (April 9, 1917). Vimy is important in Canadian war memorializing because it was the first occasion on which all four divisions of the Canadian Expeditionary Forces attacked as a single formation, and had tremendous success in terms of terrain, enemy soldiers and weapons captured. It was also an event in which 10,602 Canadians were injured and 3,598 died.

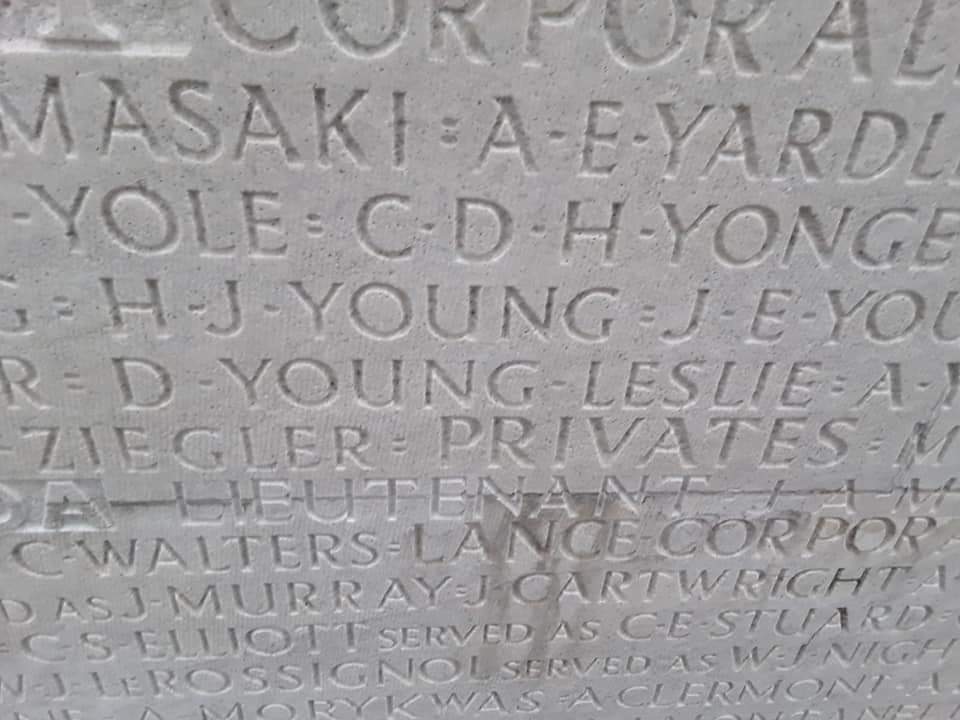

Donald’s name is recorded on the Vimy Memorial, and on a memorial in Picton, Ontario, but there is no known grave. France has many places with the name “Fresnoy”, within a 2 day’s march from Vimy, so it’s hard to know which one he died at. We don’t know how he was killed. Was it injuries sustained at Vimy? Was he a sniper who was killed by a bomb? We don’t know.

I’m grateful to my daughter, who went to Vimy in 2018, and found Donald’s name on the memorial.

I’m also remembering Donald’s younger brother, my grandfather Archibald Young-Leslie, who enlisted but did not serve overseas, because of spinal scoliosis. After the war, Arch had a promising career with Ontario Hydro, which he cut short, dismayed by their adoption of nuclear power generation. He found it unconscionable to use nuclear energy, after the horror of Nagasaki and Hiroshima. I wonder what he would say today, as fossil fuel created climate change makes nuclear power more appealing again.

Grateful that I have so few family to list on Remembrance Day.

Aghast that despite all these years of poppy-wearing and #LestWeForget, we still have war, atrocities, ethnic cleansing — WWII, Vietnam, Bosnia, Rwanda, Ukraine, Palestine, Türkiye, Syria, Sudan, West Papua…. 💔

Going to the Ceasefire for Palestine rally at the Legislature tomorrow. But more for solidarity with my neighbours and public grieving than hope that yet another peace rally will be effective at swaying the decisions of colonists, Zionists, settlers, fascists and corrupt politicians like Netanyahu, or rid the world of vile organizations like Hamas and Islamic State (created as they are by that stupid decision of Israel 1948, ongoing craven self-interests, occupation, geopolitical violence).

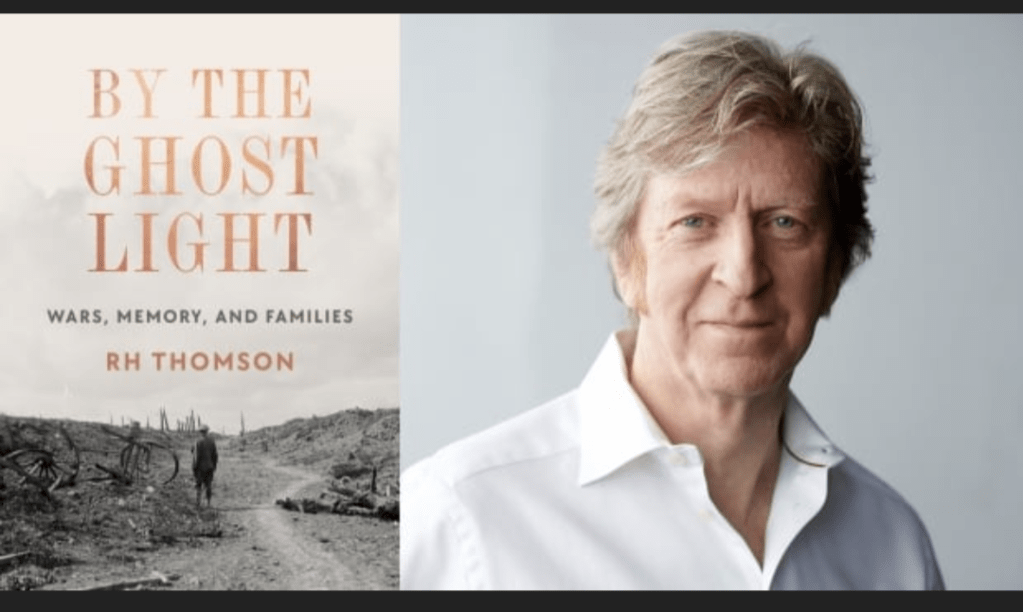

Then I’m going to buy and read R.H. Thompson’s new book. Listen to his thoughtful, magical, optimism-generating answers to The Next Chapter’s version of The Proust Questionnaire.

Optimism Day! Getting to Fully Vaccinated Against Covid-19 (a tweeted photo essay of jab2).

June 14 2021: ANTICIPATION….

I’m at the @GoAHealth immunization clinic at 12:35, for a 13:10 appointment. Parking lot full. Queue around the building. I join the queue, take the fresh medical mask & wait. “We are serving 12:40 appointments” says the announcer. I wait. At 13:10, she invites 12:50 people.

The queue is calm, orderly. But it’s hot & there’s not much shade. People all around the parking lot, in shade puddles, waiting for their time’s announcement. @ 13:17, she invites 13:00 (1pm) appointments.

The queue takes approx 20 mins to move around the building. Once in the queue, some people are facing the dilemma: wait & hope the new time is announced before reaching the door? Or get into the shade?

I feel like we’ve already had the dress rehearsal for this with Dose 1.

I’m back in my car, waiting. I’m wondering who scheduled these appointments?

It is 13:28: still serving 13:00 appointments.

Wondering: should I rejoin the queue?

13:29: “We are serving 13:10“.

I’m back in the queue, which now is only 2 sides of the building long.

Anticipation mounting!

13:41 and I’m in the door!

It’s air-conditioned inside, which is lovely. After a shot of sanitizer gel, I’m back in another queue. I’m having airport flashbacks!

13:48

Checked-in! Easier than a flight, by far. I just had to confirm health card number, type of vaccine for Dose 2, address, birth date, and then it’s a third queue.

The queue divides (unzips?) for Moderna & Pfizer. I get to watch a vaccinator on casters and a helper speak to someone with their arm ready.

Patient confidentiality preserved by this photographer (not by clinic set-up)…

14:04.

VACCINATED!!

The RN of AHS refused to allow me to photograph the shot going in. Not even with her out of the shot. She wouldn’t even hold the empty syringe against my arm for a posed / faked shot. See that red spot on my freckled arm? That’s my injection site. Her technique was impeccable.

I have to wait 15 mins.

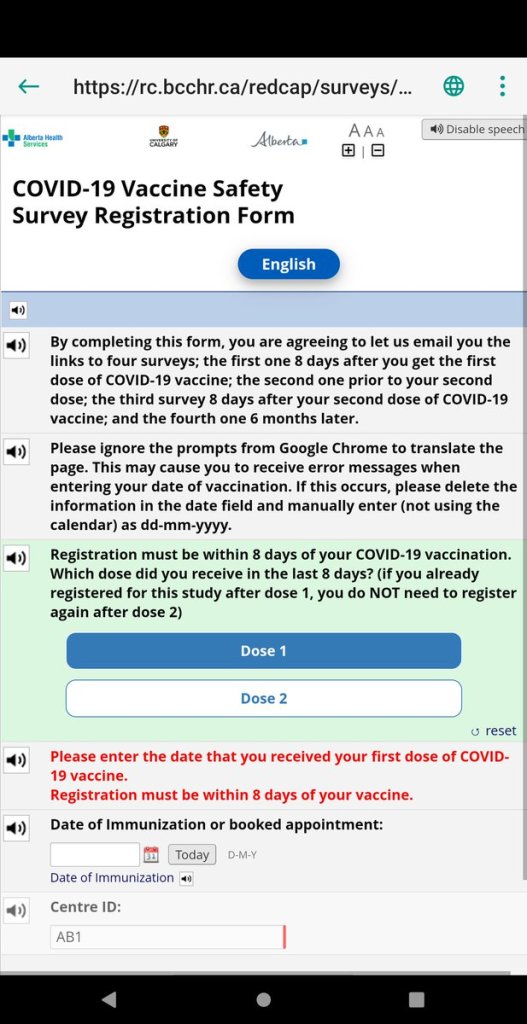

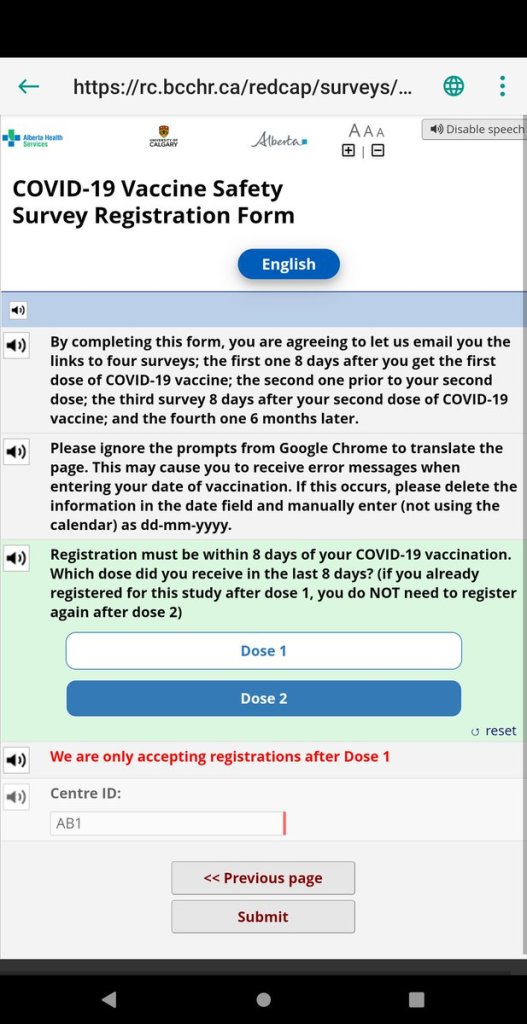

Using the time to enroll in the Covid19 Vaccine Safety Survey. It’s this, or stare at all the other post-jab people sitting in lonely cubicles.

Actually, I’m not eligible to participate. The criteria is: enrol within 8 days of Dose 1. Not accepting study participants at Dose 2.

When I had my 1st jab (at a pharmacy), I was not invited to enroll. This is unfortunate. I wonder whether it’s just mine, or all the pharmacies were not participating as recruiting sites?

14:27 Released!

Now, to see whether I’ll be one of those who experience Covid19-symptoms as my immune responders spot the novel corona virus spike protein….

June 15, 07:00

Good morning Day 1 of Dose 2 vaxed!

So far, just a very sore arm. Feels like I was punched (and, for the record, Marissa-the-Vaccinator’s technique was impeccable).

June 15, afternoon:

Starting to feel ache-y, fuzzy brain. Is it end of a long day or am I feeling my immune response kicking in?

Summary: Monday, PM: very sleepy about one pm, post-jab. Tuesday AM, arm felt punched, some swelling at injection. 15 hrs later: achy, skin felt tight, couldn’t focus on screens; 20 hrs= chilled, wrapped up in blankets. Wed AM= fuzzy; Wed afternoon, ok, but short of breath on easy exercise. Wed evening: AOK!!

June 28th: My #OptimismDay! Two weeks post dose 2. I’m as vaccinated as I can be.

This does not mean I will stop protecting myself & others. We have the DeltaVariant in Alberta. Fewer than 37% are fully vaccinated, as yet. Only 71% of Albertans have had dose one. So: I’ll still #mask indoors & in public where I can’t physically distance. And I’ll continue to hand-wash, while reciting the Star Trek intro.

#FullyVaccinated

Notes From and For the Frontlines of Academic Restructuring

Originally posted 20 December, 2020 by Arts Squared. Since first published, the University of Alberta’s General Faculties Council rejected the ‘Executive Dean’. However the position was still created, just with the title “Interim College Dean”. The “interim” part of the job title fell into disuse in about one week.

This was not intended to be an essay, not even a blog post. This began as a set of briefing notes collated for colleagues at the University of Alberta, prior to the now historic General Faculties Council meeting of 7 December 2020. That was the meeting where the university’s statutory and PSLA–mandated body was to consider the Provost’s proposal for academic restructuring, a proposal that included bundling faculties into “Colleges” and the creation of a new academic administrator position, that of “Executive Deans” who would lead the Colleges. In the days prior to the GFC meeting, the idea that the university might create Executive Deans was highly controversial. The role of an Executive Dean, as proposed by the Provost, would be to drive cost savings, and manage the shared administrative and fiscal aspects of the Colleges, while each faculty’s Academic Dean would manage their Faculty’s research and teaching affairs. Many members of the UAlberta community, academics, administrators and support staff alike, had reservations about the proposal for Executive Deans, but did not seem to understand what was driving this particular model for the restructure and cost-savings. These notes were my attempt to understand where the Provost’s idea of Executive Deans was coming from, and how the restructuring model was understood by those promoting it. They were also my attempt to draw on feedback from colleagues elsewhere who have experienced similar restructurings, similar governmental agendas for restructuring (austerity, reduction of public sector services), and similar, if not exactly the same, consultancy firms (i.e., the NOUS Group and McKinsey & Company). As an anthropologist, where the research goal prioritizes understanding “the other,” my approach was to begin by looking the horse in the mouth, so to speak. To do this, I read NOUS and McKinsey & Co.’s advisory and promotional materials, especially those referring to universities. That led me to read about McKinsey & Co. in greater detail.

Executive Deans: Understanding the “transformation” and “organizational effectiveness” backdrop

Much of the rhetoric that we have been hearing at the University of Alberta is that the university needs urgent “fundamental systemic reform,” in order to achieve the “organizational effectiveness” necessary to drive dramatic cost savings, while also “setting a bold new direction for the university of tomorrow” (see “U of A for Tomorrow”). Fundamental organizational transformation is a dramatic agenda, and UAlberta’s administration has contracted the NOUS Group to guide and manage the transformation process. The NOUS Group have a close relationship to global management consulting giant, McKinsey & Company. NOUS Group founder Tim Orton was a consultant with McKinsey & Co, and several others of the NOUS Group’s leadership came there from McKinsey & Co. (for example, directors Karen Lenane and Nikita Weickhardt, principal Gregg Joffe, and consultant Jack Marozzi appear in an easy Google search). Much of what we at UAlberta see and hear about restructuring can be traced to advice from McKinsey & Co.

McKinsey & Co. recognize that large scale organizational transformation fails about seventy percent of the time. They advise that universities often fail to transform because university leaders fail to hold the course. In their view, while university leaders may be “gifted educators, researchers, fundraisers, and academics,” they

“have little experience leading the transformation of a large, complex enterprise. Complicating matters, stakeholders often cling to deep sentiments about their institutions and their school traditions, which impedes change. And the shared governance structures at most universities makes it even more difficult to act quickly and decisively. When leaders encounter inevitable resistance, it’s not surprising that they often relent, and the project stalls, is abandoned, or becomes mired in a long implementation with poor results”. (See McKinsey, “Transformation 101.”)

In this perspective, Executive Deans are considered efficient because they evince —on paper— the “clear chain of command” that any general would appreciate. They make an organizational chart look neat and tidy. Business people speak of this “chain of command” as a way of assuring accountability. McKinsey & Co. have recommendations for “managerial spans of control” (number of direct reports) based on archetypes of managerial roles and work complexity—by time, standardization, variety, and skills needed. At the University of Alberta we are familiar with this type of task accounting in the form of the Hay points currently used to determine the ranks and salaries of administrative staff. More recently, we have been hearing about benchmarking data being provided to a company called UniForum, which UAlberta has contracted to help drive administrative restructuring and ‘savings of scale’ by reducing duplication of tasks across multiple units.

According to McKinsey & Co. the typical number of direct reports for a corporate Vice-President is three to five, and for the role beneath the V-P, six to seven. So when the Provost speaks of a scenario with a linear chain of command consisting of three Executive Deans and three Faculty Deans as his direct reports, it seems he is revealing the influence of McKinsey’s organizational thinking on his idea of the ‘right number’ of Faculties.

McKinsey & Co. claim that “rightsizing” —i.e., changing the type of manager or spans of control— “can eliminate subsize teams, help to break down silos, increase information flow, and reduce duplication of work …. [It will also] decrease the amount of micromanagement in the organization, [and create] more autonomy, faster decision making, and more professional development for team members.”

The promise is that for UAlberta, “rightsizing” will, in addition to cost savings, offer a pathway to “nimbleness” and “interdisciplinarity,” and may be good for career growth and job satisfaction. However, is rightsizing the right process for UAlberta? And at what cost?

Executive Deans: Understanding the structural pushes and challenges

The same McKinsey article that recognizes that large scale transformation tends to fail most of the time and that university leaders have a tendency to resist such transformation out of preference for things like collegial governance, also advises that “[a] key finding of our work is that while a reasonable degree of cost management is usually necessary, it’s more important to focus on improving student outcomes and identifying new ways to diversify and grow revenues” (emphasis added). We, in the opening salvos of restructuring at UAlberta have heard little about ways to diversify or grow revenues. Frankly, in the Canadian public universities system, “growing revenues” has limited options. Our post-secondary education system was designed to benefit the public, not generate profits within the universities themselves. The profits are accrued to society, with a better educated populace who, in knowing how to think critically and analytically, are better at self-governing, bring intelligence and reflection to their roles, earn better salaries, pay more taxes, and engage more civilly. The appeal of a company like McKinsey & Co. to a government seeking to reduce spending on universities lies in its provision of “strategies . . . that can help universities reduce their dependence on the typical two largest sources of revenue —tuition and government grants.”

Ironically, while McKinsey & Co. advocate a fairly shallow organizational hierarchy with a decreased distance from senior leaders to the front line, the organizational structure they promote actually creates a bimodal hierarchy that separates the senior leadership from those who actually produce value (the professoriate), by eliminating the middle managers (Associate Deans, for example). This leaves the highest echelon free to dictate decisions (or “be nimble”) and, coincidentally, to amass the bulk of an organization’s remuneration. This form of bimodal hierarchy, and McKinsey & Co.’s position in promoting it, has recently been blamed for destroying the middle class of North America (Markovits, 2020).

The Executive Dean model involves a structural hierarchy where authority derives from the top. Loyalty is therefore necessarily aligned with the Provost, President and Board of Governors, not, expressly, with the professoriate, nor even the students of the Colleges the Executive Deans would lead. This hierarchy is expressly anti-collegial in its governance model. Anyone who has studied chiefly social systems knows that good chiefs are those who recognize their dependence on their people, and who actively redistribute wealth. But with too much hierarchy, distance from the base, limited numbers of people with direct access to the “chief” and few with similar rank or authority (i.e., with no “middle”) comes more autocratic control. In UAlberta’s case, that greater autocratic control will come from the Provost’s office. Leadership will become more top-down, even less democratic, less a cohort of peers. In other words, corporatized.

When coupled with performance-based funding and key performance indicators (“KPIs”), we end up with no investment on the part of the senior leadership to resist the corporatized direction, and leaders who prefer to think of themselves not as academics but as CEOs. With Executive Deans we would see an expansion of the senior administrative leadership. Examples from other locales demonstrate actually this mode gainsays the goals of cost-saving and organizational effectiveness UAlberta is purportedly seeking.

I am quoting here from a recent research report on British and Australian senior leadership salaries:

The shift in the UK and Australian universities from collegial to more corporate forms of operating has engendered a corresponding shift in governance from stewardship to the agency. Professional management functions have come to the fore in the pursuit of business objectives and VCs [Vice Chancellors or the equivalent of university Presidents in Canada] both see themselves and are seen by others, including governments and government agencies, as chief executive officers. A significant uptick in V-Cs’ remuneration has occurred relative to other academic salaries. Market-based salary setting mechanisms, such as benchmarking, appear to drive these increases. (Boden and Rowlands, 2020)

See a synopsis of Boden and Rowlands’ argument in The Conversation, Australia.

The Australian and United Kingdom Experience

According to one Aussie colleague, “In Australia, the executive academics (Heads of department and up) do not teach and have no research expectations. They are contracted on a bonus based system. There is zero transparency about remuneration: nobody knows what anybody’s agreement is and there are many backdoor deals done” (Name withheld for confidentiality). My Aussie colleague describes this as another way of undermining any collegiality.

With Executive Deans, in fact all of the senior leadership, unless the executives’ performance indicators and budget structures are carefully wrought, there is little in the way of structural mechanisms to keep Executive Deans from becoming more like Provosts, less like colleagues, not even Deputy Provosts or Associate VPs. Boden and Rowlands (2020) recommend “maximum fixed ratios between vice-chancellors’ remuneration and average academic salaries.” But who in the UAlberta structure would or could make that happen? The Provost? Not the Executive Deans. It is doubtful that even this Board of Governors, despite their concern with austerity, would adopt that remuneration model.

Following from the McKinsey & Co. material on Chief Transformation Officers, and the experience of academic restructuring in Australia and the UK, Executive Dean positions will be filled by executives who have ceased to be primus inter pares (first among equals) and have become, rather like university presidents in Canada are now, former academics who behave like corporate CEOs. With that, there is great risk that Executive Deans will became more and more expensive.

The expense of Executive Deans will not necessarily be because they are great managers for their institution, colleagues, and students. Research from the UK has demonstrated that managerial efficiency fails as a determinant of Vice-Chancellors’ remuneration. Factors like student participation and research grants success don’t explain the remuneration increases either. See Bachan and Reilly, 2015. Surprise, surprise, age, size, and reputation of the institution are more reliable predictors of V-C pay. See Virmani, 2020.

With performance measures that focus on annual rankings and corporate fund-raising rather than faculty, staff and student satisfaction, you end up with a cohort of executives whose career path is not based on growing within a university community to which they are dedicated. Instead, these senior academic administrators flit from one university to another, increasing their remuneration as they move up the ladder in terms of institution reputation and size. (That’s one way to understand the imperative to “be nimble.”)

The Outlook for University of Alberta for Tomorrow

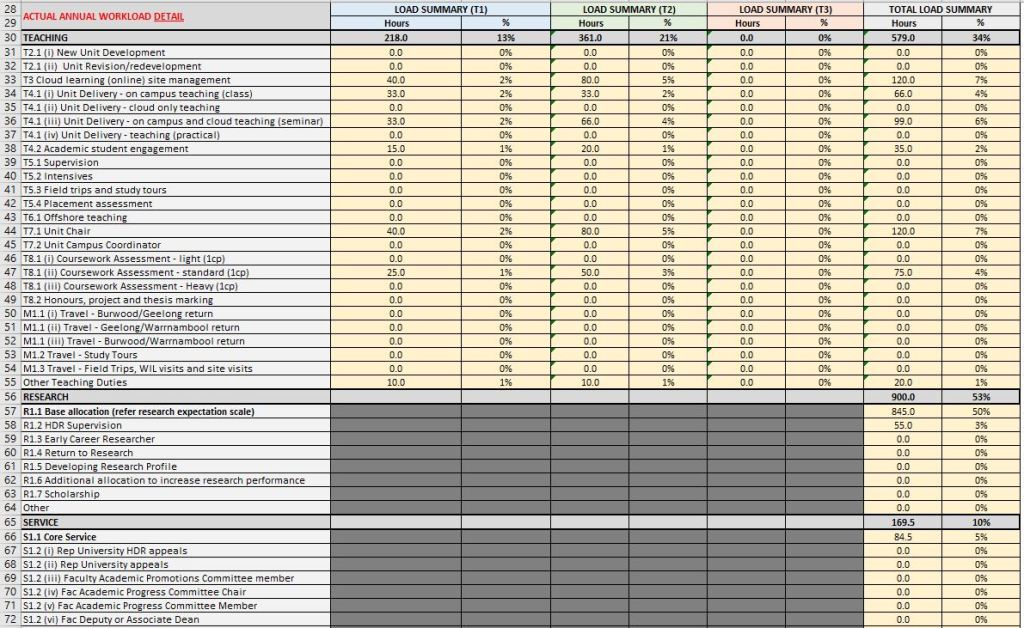

Whence will come the cost savings UAlberta needs? They’ll come from draconian measures, such as vertical cuts, but beginning with cuts of academic teaching and support staff positions, and downward pressure on the professoriate via managerial mechanisms such as the Faculty Evaluation Committees, algorithms that determine academic performance, and Key Performance Indicators. A colleague shared a real prof’s workload evaluation spreadsheet, from a major Australian university. I’ve redacted the name.

My colleague sent the Australian prof’s workload summary with this note:

Hi Heather,

This was provided by a colleague. Read and weep.

Note in the research tab how different research publications are weighted as “points”. A minimum number of points must be achieved each year or the algorithm under the teaching calculation is changed to ensure additional teaching hours are performed. So for an ordinary senior lecturer (not a prof) to keep your research allocation at 40% (a typical 40-40-20 workload distribution) you would need to produce 7 research points a year – that is 7 book chapters, or 1 book and 2 chapters, and so on. A prof would be expected to achieve 11 points – so two books and a book chapter. Obviously none of this is sustainable if even possible. So the effect is that everybody does a LOT of teaching (70-10-20)…

This is what is really meant by “performance-based” universities.

Cheers

[name withheld]

Buzzwords Decoded

It is unfortunate that two wonderful concepts—nimbleness and interdisciplinary— have been captured by the Provostial rhetoric and transformed into buzzwords.

“Nimbleness” is code for the freedom to expand the precariate and make vertical cuts.

“Interdisciplinarity” is code for merging departments.

Recently, those of us observing the UAlberta’s Board of Governors’ meeting on 11 December 2020 were offered another buzzword to consider: “Laser focus.” This is less difficult to interpret. Laser focus is code for relentless inflexibility, autocracy, and hatchet-wielding, all in the name of KPIs. Actions associated with laser focus include denying collegial governance, breaking collective agreements, pitting departments and colleagues against each other, creating chilly workplaces, and hailing the hatchet-wielding executives with titles such as “Chief Transformation Officer.”

The McKinsey Touch

Look soon to see McKinsey-inspired expansion of the mandates for the Board of Governors.

For more background on McKinsey & Co. I recommend Duff McDonald’s The Firm (2014), and investigative journalism in The New York Times and The Independent.

After learning all this, I have one or two questions more. Why is it that management consulting firms only offer universities one model for organizational effectiveness, leadership, and transformation, a model based on a capitalist corporation? Instead of accepting a huge failure rate in transformations, why not offer universities an organizational structure more similar to what a university is? Yes, our university has to change. But does it need to be corporatized? Why aren’t our current leaders demanding —of themselves— expertise, higher degrees, MBAs even, in co-operative management? Why are they not demanding of the consultants they hire —NOUS, McKinsey— something that respects the collegial governance system and its longue durée of successful production and sharing of innovation, creativity, critical thinking, and knowledge?

The answer to these questions may lie far from the Alberta prairies, at Harvard’s Business School.

Finally, for more on McKinsey & Co, listen here:

The Flygskam Scam

Flygskam :: Flight guilt

December 6, 1989 & 2017; The Resilience of Violence, 2.0

28 years ago today; I was pregnant, happy, optimistic for my child, who was being born into a world that had just breached the Berlin Wall. It seemed like peace was breaking out all over. And then, Dec 6. Montreal. L’Ecole Polytechnic.

It was a terrible shock. Not just that a single shooter would attack students at a university. But that he would specifically order classes to separate into groups of male and female, and then shoot, murder, slaughter, the women only. And then repeat in other classes.

Suddenly, the entire nation, was confronted with a terrible truth: as people listened to the reports, some realized they’d momentarily expected -and accepted- the idea that the shooter might separate the victims by sex, so that he could shoot the men. That he targeted the women was a surprise, an affront.

The tragedy of L’Ecole Polytechnic gave Canadians a double shock: We realized our attitudes to violence had been blunted by patriarchal assumptions that included the horrid acceptance that males were legitimate targets for violence. Equally, our understanding of violence against women had been dismally, willfully, complicitly, naive. The value of feminism as a necessity, even as it was being described as the murderer’s motivation, was confirmed. The optimism of Berlin was washed in the horrors, the guilty insights, of Montreal. 22 days later, I gave birth to a daughter.

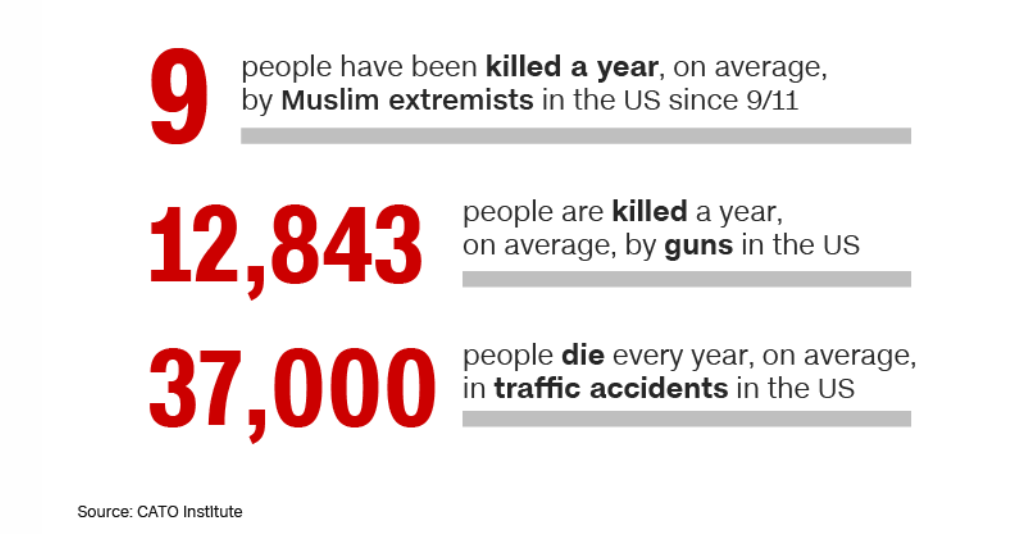

Now, 28 years on, we have Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls (& men), and Black Lives Matter, because people of colour are vastly more likely to be killed by the state, or have their deaths ignored by the state. We have the #MeToo campaign, and Time Magazine has declared the “Silence Breakers” to be their Person(s) of the Year, because so many women are OVER being sexually harassed or assaulted (or both). Violence Against Women has been raised to iconic, professionalized status. It is now possible to use the acronym of VAW and be widely understood while condemning patriarchy, the ubiquitous and resilient inequities between sexes, and while arguing for services, policies, legislation, and/or education to mitigate VAW. Good steps have been taken. But not enough, else all the women – myself included – who wrote #MeToo on our social media, and the Silence Breakers would not have had any silence to break. But just as bad is the fact that unlike in 1986, when it seemed like peace was breaking out all over, we have violence expanding: wars in Syria, Yemen, refugee crises in Europe, North Africa, and most recently Myanmar and Bangladesh (and not enough being said about the violence in refugee camps and the trafficking of child refugees), the violence in Mexico… it has only been a year since Americans voted in a man who bragged about his history of sexual harassment and assault. Now they are about to send another multiply-accused pedophile to the Senate. While the USA has banned immigrants from predominantly Muslim nations on the grounds of violence-prevention, they have themselves allowed an average of 12,843 people to be murdered with, and another 20,000 (average) to suicide with, a gun.

Violence, is resilient.

As I wrote in 2015, in the first version of this post, acceptance of violence itself has not moved on much from the guilty horror of 1989. Mothers’ children continue to be slaughtered. Today, as every Dec 6, I condemn the craven political decisions that permit the means for violence; I mourn for those mothers who suffer the catastrophe of violence against (or by) their child, and offer a grateful whew to the luck goddess that I am not in their cohort.

[Image credit: The European Danse Macabre, Alberto Martini, 1915, via @LibroAntiguo ]

Failing The Moral Test: Canadians Must Redress Our Nation’s Abuse Of Children

the moral test of government is how that government treats those who are in the dawn of life, the children*

On Valentine’s Day, 2017, Justice Edward Belobaba of the Ontario Supreme Court ruled that the Canadian government breached agreements and failed in its responsibility to indigenous peoples, for its part in a child-welfare program that saw thousands of Ontario’s children removed from their parents, communities and cultures. Now referred to as the “Sixties Scoop”, between 1965 and 1984 some 16,000 children deemed by provincial social workers to be ‘at risk’ were apprehended from their parents and communities, then fostered or legally adopted by non-indigenous families. The Ontario protocols became the template for other provinces, ramifying indigenous families’ distress across the country. In many, possibly most, cases the parents who had their children apprehended were themselves victims of a prior form of state-sanctioned kidnapping and enfranchisement: the residential school system. If the parents were not themselves survivors of residential schools, perhaps suffering the now-recognized symptoms of PTSD or abandonment trauma, they were likely subject to poverty, poor education, underemployment, and the generalized public discrimination and ‘anti-Native’ racism that was the default in mainstream society until very recently.

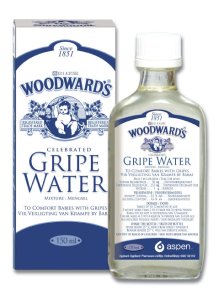

During the Sixties Scoop, even if a social worker was not stigmatizing indigenous parents and children, and was trying to apply child welfare guidelines evenly to all cases requiring intervention, the parenting assumptions penalized at the very least poverty and denigrated non-European (WASP) traditional practices. Consider these scenarios: A mother of English or French or German ancestry could buy Woodward’s Gripe Water from the local pharmacist and use it to sooth her cranky infant. A mother of Cree, Mohawk or Anishnaabe ancestry who made a tisane including dill or fennel, sugar, baking soda, and watered gin could be accused of providing alcohol to a minor, be declared unfit as a parent, and have her child removed. Yet commercial preparations of gripe water had an alcohol content ranging from 3.6% to as high as 9%, even into the early 1980s (Blumenthal, 2000). A case of domestic abuse with a white family would see the police either ignore a woman’s complaints and leave her and her children with the abuser, or help them get to a shelter; with an indigenous family, it could lead to seizure and permanent removal of the children from their entire extended kindred.

the local pharmacist and use it to sooth her cranky infant. A mother of Cree, Mohawk or Anishnaabe ancestry who made a tisane including dill or fennel, sugar, baking soda, and watered gin could be accused of providing alcohol to a minor, be declared unfit as a parent, and have her child removed. Yet commercial preparations of gripe water had an alcohol content ranging from 3.6% to as high as 9%, even into the early 1980s (Blumenthal, 2000). A case of domestic abuse with a white family would see the police either ignore a woman’s complaints and leave her and her children with the abuser, or help them get to a shelter; with an indigenous family, it could lead to seizure and permanent removal of the children from their entire extended kindred.

It was the mundane level of hypocrisy, the willingness to assume that indigenous cultures’ parenting practices were by default inadequate and dangerous relative to ‘modern’ mainstream (a.k.a. white) society, and the wider implications and ironies of that attitude, that spurred me to write the following letter, in 1998, to Michael Enright and Avril Benoit of CBC Radio’s This Morning:

Date: Mon, 23 Mar 1998

To: thismorning@cbc.toronto.ca

Subject: Spock’s influenceAs a mother and a social anthropologist specializing in mothering and the influences of North American medical personnel in everyday life, I listened with interest to your panel of four mothers discussing their use (and non‑use) of Benjamin Spock’s Baby and Child Care [originally published 1946]. Sheila Kitzenger and Sherry Thurren were also interesting, especially in their discussions of the context of maternal advice at the time that Spock was writing: his book was indeed a revolution for its time, in that it confirmed a mother’s abilities to handle situations, and advised a less regimented, disciplinary form of baby care, with more expressive loving from parents. However, the one question I kept expecting to come up was never asked: “When everyone else in the medical establishment was advocating discipline, routine, formula over breast-milk, and telling mothers that they needed a doctor’s advice for all aspects of an infant’s care, where did Benjamin Spock get his path-breaking ideas?”

The answer would have been somewhat surprising, certainly to the thousands of American and Canadian families who do not know that the revolutionary child care advice they faithfully followed, and thought of as resulting from North American medical scientific breakthroughs, was in fact heavily modelled upon Polynesian and other First Nations’ child rearing practices. Benjamin Spock’s ideas came out of anthropology, not medicine.

Benjamin Spock was the pediatrician to the famous anthropologists Margaret Mead, Gregory Bateson and their daughter Mary Catherine. As your listeners may know, Margaret Mead’s first book, Coming of Age in Samoa [1928], focused on child rearing in Polynesia. She later did similar research in North America and other parts of the Pacific as well. Mead was tremendously influential in areas of social policy in the USA from 1928 to after WWII, but not all of that influence was overt. As her daughter later wrote about Mead: “Margaret’s ideas influenced the rearing of countless children, not only through her own writings but through the writings of Benjamin Spock, who was my pediatrician and for whom I was the first breastfed and self‑demand’ baby he had encountered” [from With A Daughter’s Eye, 1984, William Morrow & Company, Inc].

It is ironic that the great influence aboriginal peoples have had in contemporary North American cultural and medical practice has been so disguised. But there is an even greater irony here: while at least two generations of white, middle class parents were following re‑packaged aboriginal people’s parenting practices and choosing to nurture and indulge their children for the sake of their good psychological development, First Nations parents were being forced to send their children away to residential schools: There, aboriginal children were subjected to the very discipline, authority and cold regimentation that Mead and Spock helped to discredit.

And we now have the temerity to ask why so much psychological damage is rampant in some First Nations communities, and how is it our concern!sincerely,

Heather Young Leslie

I wish I had been more forceful in my 1998 letter. I wish I had spoken of racism, tragedy and abuse rather than ironies. At the time, I feared a more candid letter would not be read on air. It has taken so long for an appetite for the truth about generations of Canadian state-sponsored violence against children and families to come into the general discourse (even now, I suspect it is only the liberal-Canadian public who are paying attention). When Justice Belobaba agreed with the complainants that the Sixties Scoop resulted in widespread psychological traumas for the children, their extended families and communities, leading to psychiatric disorders, unemployment, violence, incarceration and suicide, he was affirming what Indigenous-rights activists have been saying for a very long time, often to deaf or uncaring ears. Yet beyond the thousands of individuals, mostly children, harmed, entire Indigenous nations have suffered as generation after generation lost fluency in their languages, ability with ceremony, technical making and survival skills, intimacy with traditional territories and kinship networks; many simply died. Colonialism and colonization is war that never stops killing.

Although Canada as a nation has engaged with the recent Truth and Reconciliation Commission‘s investigation of the residential school system, and now publicly seeks ‘reconciliation’ with Indigenous peoples of Canada, and while our Prime Minister has promised to honour treaties and enact a ‘nation-to-nation’ relationship, there is much that has yet to happen before true reconciliation can happen. While Carolyn Bennett, the current federal Minister of Indigenous and Northern Affairs, has publicly stated that the federal government will not appeal Justice Belobaba’s ruling, her Ministry has spent millions vigorously applying every loophole they could to refute another child welfare case, this one brought to the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal, regarding the Government of Canada’s deliberate unfunding and policy blocking of First Nations Child and Family Services. The Tribunal’s Decision was that Canada, via the Ministry of Indigenous and Northern Affairs, is purposefully discriminating against “163,000 First Nations children and their families by providing flawed and inequitable child welfare services to First Nations children and by allowing jurisdictional disputes between and within governments to cause First Nations children to be denied or experience delays when seeking to access essential government services available to other children“. Despite claiming to welcome the Tribunal’s Decision of January 26 2016, Carolyn Bennett’s Ministry continues as of Feb 2017, to be non-compliant with the legally-binding ruling of the Tribunal. Further, she is speaking about trying to avoid a court-mandated settlement in the Sixties Scoop class action. The 16,000 complainants have requested damages of $85,000 each, less than one year’s middle-class salary, for a total of $1.3B. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s Cabinet and Finance Minister Bill Morneau have not, as yet, prioritized indigenous reconciliation and fair costs for federal responsibilities in the budget for 2017.

Most Canadians do not know we are all “Treaty People“, nor how much has been taken from our treaty-partners, how much loss, pain and trauma still reverberates, though I think most people can empathize with having a grandparent or spouse with PTSD, with the fear of loosing one’s home, or the horror at the mere idea of having a child kidnapped, disappear, or commit suicide. While there is much resilience and goodwill within Canada’s Indigenous communities, there is much understandable anger and resentment too. The solution goes beyond the political will to admit wrong-doing, apologize and budget the true costs of complying with historic treaties and Supreme Courts’ and Human Rights Tribunal findings, though those are essential measures. There is reaching out by everyday Canadians to be done too. A good place to begin is to learn what it is we don’t know: even those who say they are allies of Indigenous peoples, are supportive of the reconciliation cause, or are anti-racist, can learn more, and should. This is a scenario where what you don’t know can hurt someone, probably a child and or her/his family.

I have three recommendations to start you off: The first is that all Canadians, young and old, multi-generational settler-descendent to first generation immigrant to refugee, read the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s reports, especially their Calls to Action. The second is to view the National Film Board‘s We Can’t Make the Same Mistake Twice, Alanis Obomsawin’s latest documentary, which follows and makes easy to understand, the many-years history of the Human Rights Tribunal’s hearings and eventual findings. The third is to take the University of Alberta’s online course Indigenous Canada (enrolment begins March 2017; it’s free to audit, cheap to get a certificate). These are things that Community Leagues, Rotarians, Lion’s Clubs and other service organizations, book clubs, walking and yoga groups, church parishes, curling and hockey and baseball teams can do together. These are easy initial steps to reconciliation that all non-Indigenous Canadians can, and should, take.

That’s not the end of course. We all must know and agree to respect the Treaties that the nation-state of Canada is built on; learn what is in the treaties governing where we live now and where we were born (if there even is a treaty), lobby our provincial and federal governments to stop asking First Nations for just a bit more of their land, water and wildlife habitat. A “nation-to-nation” relationship is like consenting to sex: “no” must be respected; it doesn’t mean “Try harder to convince me” or “If you say no, we’ll just take it”. In general, we must be mindful of the place we inhabit, and what impact our actions have on our treaty partners, wherever we live. This is going to be tough for those who have benefited from privilege and not had to recognize treaty responsibilities, certainly. Reconciliation is a long, slow, multi-party process. It requires so much more than “I’m sorry”. Now is the time for the non-indigenous peoples of Canada to paddle the boat. Because, to recycle a saying from my youth: “If you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem”** and this problem is one that persists in abusing children and their families. That’s not what we mean when we proudly exclaim our “Canadian values”.

*Hubert Humphrey. Remarks at the dedication of the Hubert H. Humphrey Building, November 1, 1977.

**Eldridge Cleaver. Presidential candidate speech at UCLA, April 10, 1968 (Listen at 51:05 mins), also speech to the San Francisco Barristers’ Club, September 1968.

A Screed* for 7/7/16

Police violence at a #BlackLivesMatter protest in New York City. Overshadowed by a different sort of violence, a vigilante-payback murderous sort of protest, in Dallas.

Heartbreak. Horror. Anger. Shock.

Obviously, there will be lots of palaver about what needs to change. Gun culture for example. Prosecuting those who abuse the power of their position, who fail to serve / protect. Training (re-training) (better training) (anti-racism-training) of police.

And maybe before the training, recruitment, but:

How to entice better recruits? What sane person wants to work in a racist, sexist, phobic organization?

And while we in Canada may subtly congratulate ourselves for not having the (scale of) problems that they have in America, let’s not forget we too have discrimination and sexism

Our RCMP are but one recent example.

*A Screed is a song of protest, of vilification.

The Lost Jingle Dress

The Lost Jingle Dress is my first ‘published’ piece of creative nonfiction. The story lauds the small, tight-knit community of Jasper, Alberta. I wrote it in 2014, and it was performed by Stuart McLean in 2016 for the CBC Radio program Vinyl Café. It aired in the story exchange segment of the “Indigenous Music” episode of June 3 & 4, 2016.

The Lost Jingle Dress is my first ‘published’ piece of creative nonfiction. The story lauds the small, tight-knit community of Jasper, Alberta. I wrote it in 2014, and it was performed by Stuart McLean in 2016 for the CBC Radio program Vinyl Café. It aired in the story exchange segment of the “Indigenous Music” episode of June 3 & 4, 2016.

Stuart McLean’s performance of The Lost Jingle Dress is archived in the Education and Research Archive of the University of Alberta’s Libraries, here. Forgive the amateurish sound production. This version was recorded from the public radio broadcast onto a private-owned iphone 5 in m4a format.

Myths perpetuated by the Ghomeshi trial (re-blog)

(Re-blog from PressProgress.ca)

A Toronto court heard final arguments Thursday in the trial of former CBC Radio host Jian Ghomeshi.

Ghomeshi is charged with four counts of sexual assault and one count of choking to overcome resistance related to allegations brought forward by three female complainants.

While the defendent’s guilt or innocence will be determined by a judge based on evidence presented in court, Ghomeshi’s defence strategy has been widely criticized, with suggestions the aggressive cross-examination of witnesses in the high-profile trial is revictimizing the complainants and discourages women from reporting sexual assaults in the future.

Now, some question if Canada’s criminal justice system is “structurally ill-suited” to deal with sexual assault cases?

Here’s what experts and observers have to say about five of the more dangerous myths the Ghomeshi trial has pushed into the public square:

1. “Consent can be implied, retroactively”

Throughout the trial, Ghomeshi’s lawyer, Marie Heinen, has sought to raise doubts about the relationship between the complainants and her client after the alleged assaults took place.

In all of this, Macleans’ Anne Kingston observes, “the defence appears to be trying to establish some sort of retroactive implied consent, which, of course, is moot: at the time of the alleged assault, the future hadn’t occurred.”

However, Canadian law is quite clear that this is ultimately irrelevant to the issue of ‘consent’.

“If you examine this [Ghomeshi] trial,” says University of Ottawa law professor Constance Backhouse, “basically because the victims gave consent to some things — before, during and after the alleged non-consensual behaviour — we’re all making assessments that they are not believable about the non-consensual part.”

And in the eyes of the law, none of this may matter: “the Supreme Court has said that a person cannot consent to an assault that causes bodily harm,” says University of Toronto law professor Brenda Cossman. “If a sexual activity causes bodily harm, a person cannot consent to it.”

Recent polling done by the Canadian Women’s Foundation found that while 96% of Canadians agree sexual activity between partners must be consensual, over two-thirds of Canadians (67%) do not understand the legal definition of ‘consent’.

2. “Survivors go directly to police after an assault”

Heinen also questioned why one complainant did not go directly to police after the alleged assault.

“I didn’t go to the police because I wanted to go home,” the woman answered. “I didn’t go to police because I didn’t want – this,” referring to testimony before the court.

That response is consistent with statistics on sexual assaults in Canada. In 2014, Statistics Canada reported only 5% of all sexual assaults in Canada are reported to police.

“Sexual assaults perpetrated by someone other than a spouse were least likely to come to the attention of police,” another report from Statistics Canada adds, with “nine in ten non-spousal sexual assaults were never reported to police.”

3. “Survivors never go back to their abuser”

Heinen introduced evidence suggesting one complainant’s contact with Ghomeshi after the alleged assault challenged the credibility of the allegation itself.

This isn’t necessarily surprising, experts say. Survivors of abuse typically “manage the violence” through a range of responses to a traumatic experience, including “denial” and “self-blame” before they actively seek help.

“Many leave and return several times before their final separation,” reads literature prepared by the BC government for victim service workers. Some reasons include emotional attachments to the abuser, emotional abuse, threats or fears of continued violence, social and cultural pressures, or financial dependence, to name only a few.

As Keetha Mercer of the Canadian Women’s Foundation told Chatelaine:

“There are many reasons why a survivor would contact her abuser. These may include wanting to get closure or addressing what happened. Many survivors struggle to break off contact with their abuser because the nature of abuse includes undermining their self-esteem and confidence. They may feel controlled by their abuser, which is a hard feeling to shake even after they have left.”

4. “Women lie about being sexually assaulted for fame and attention”

Ghomeshi’s lawyer suggested one complainant’s allegations were motivated by fame and attention, stating she was “reveling in the attention” and pointing out how her number of Twitter followers had “skyrocketed.”

Except the trial process is arduous, often re-victimizing survivors. And as Toronto lawyer David Butts points out, the current system is “basically trial by war,” so who would volunteer to put themselves through such a distressful process?

“That is probably the worst thing to do to complainants who are coming forward to talk about very intimate and distressing violations of their sexual integrity … Moving away from an adversarial model, I think, is going to be necessary because look at the Ghomeshi trial — who would voluntarily put themselves through that?”

Not only that, but only 42% of sexual assault trials end in a conviction. 47% see charges stayed or withdrawn.

5. The stereotype of the “perfect” victim

Ghomeshi’s defence has also attracted criticism for its “extreme focus on inconsistencies” in the complainants accounts of events, “including information that may appear to some as irrelevant,” and using these to suggest complainants are stricken with “false memories.”

Macleans’ Anne Kingston says this strategy of asking “very personal questions” is “pretty extraneous but just poked holes in issues that should have nothing to do with the charges at hand.”

“It’s totally irrelevant to whether she wanted to be punched in the face,” says UBC law professor Isabel Grant, who says the focus on inconsistencies is irrelevant to the issue of consent, but instead plays into stereotypes about women’s sexuality.

Canadian novelist Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer observes that Heinen’s cross-examination implies “that the woman has to be this hygienic, innocent, perfect bystander in these cases” – constructing an impossibly unrealistic image of what a credible victim looks and sounds like, irrelevant of the facts of the case.

“She seems to articulate that they wanted it, that they produced the violence,” Kuitenbrower adds. “And then when it happened, they came back for more.

Tags: #Sexual Assault #Violence Against Women #feminism #Jian Ghomeshi #gender equality #Criminal courts

Source:

Smoke + Mirrors: Marie Henein’s lawyerly tactics in defense of Ghomeshi

[Feb 9, 2016. Some thoughts on the Ghomeshi trial, as the third complainant’s testimony and examination is completed, and as we wait for Judge Horkins to rule on admissibility of a fourth witness]

We knew that the complainants alleging assault and other charges against Jian Ghomeshi would face severe, rigorous questioning intended to discredit their testimony, from highly credentialed and skilled lawyer Marie Henein. As a dear friend and one-time courts reporter has pointed out to me, society needs this to happen. We want a defense lawyer to be vigilant and ardent; a person’s liberty is at stake. We don’t want to live in a society where a state lawyer does not have to prove beyond a shadow of a doubt that an accused should be convicted.

However there is questioning to discredit testimony and there is “whacking”. The latter is a nefarious tactic which occurs almost exclusively in sexual assault cases. It depends on aggressive, verbal accusations, double-negatives and sexist stereotypes. The goal is to confuse and intimidate a witness so that what they say isn’t what they mean or want to say. There are many who are questioning the ethics of this tactic, noting that it is something that, like torture, fails to provide actual truths. Whacking also depends on the legal system’s assumptions that linear, chronological testimonies can be elicited from participants in traumatic events and that such ‘clear’ testimonies are more credible. Therefore, if a witness’ verbal re-telling of a traumatic event can be deconstructed, it is likely false, or exaggerated. This expectation is based on false assumptions rather than research evidence about how traumatic memory actually works and how women often react during assault. It depends on negative stereotypes about women and victims of sexual assault in particular.

So, to recap, whacking is a courtroom tactic of intimidation particularly popular in defense of sexual assault, which is intended to discredit a witnesses’ and complainant’s testimony.

Ghomeshi’s lawyer, the brilliant and fearless Marie Henein, is renowned for her whacking skill. In the Ghomeshi case however, I think Henein’s intention is to do more than just discredit the testimony through intimidation. There seem to be three key legal points that the case hinges on (I’m not a lawyer, but this is what I understand from reading the criminal code, and various pundits and researchers): First, was the violence consensual, from the beginning and during; second, is there a pattern, i.e.: ‘similar facts’ that can be permitted to weigh in a verdict; third, were the ‘serious harm’ actions really severe enough to be the kind of harms our criminal code says we cannot actually give consent to? I think what lawyer Henien’s strategy is a five-part smoke and mirror trick designed to address these three points of law, and one point of judicial hubris:

1) She is trying to imply that Lucy Decoutere and the two other complainants gave on-going consent, that they welcomed and therefore participated in the hitting, choking, hair-pulling, etc. This is intended to distract the judge from the point that there is no evidence of prior consent in the first instances.

2) She is trying to prevent the judge (and public) from recognizing and believing the complicated psychology of how the brain reacts to and processes trauma, including how women post-assault may seek approval from the aggressor or try to remediate a sense of their unacceptable ‘victimhood’ by choosing ‘participanthood’ post-hoc. This does not gainsay the fact that prior and/or on-going consent had to have been given, and that failure to deny consent is not the same as giving consent.

3) Significantly, Henien seems to be trying to elide the point that Canadian law doesn’t actually permit us to consent to serious harm.

4) She is also trying to circumvent the ‘celebrity as authority figure’ factor that Ghomeshi represented for the complainants: the fact that he was a highly regarded personality with influence in the media-arts-entertainment industry and the women were in early-career stages with aspirations in that business meant that Ghomeshi’s actions were extra compelling, in both his potential and effect as a perpetrator. He had the glamour (in the old Celtic sense of disguising evil with beauty). I wonder if Monica Lewinsky might not have something to say about the complicated emotions that happen when one thinks of one’s idol as a friend, or even romantic partner?

5) More speculatively however, and this is where the mirrors become truly smokey, I think Henien is playing a long head-game with Judge Horkins. I think she is trying to trade on the rather fuzzy boundaries as to what actually consists of consentable sexual violence, and to push the judge into fearing making a ruling that establishes a new precedent, but could be overturned on appeal. Judges hate having rulings overturned and Henein is trying to make the judge concerned about his own legacy.

In the latter (5), I suspect Henien could succeed, simply because Ghomeshi and his past ‘intimate partners’ do not seem to me to be credible as exemplars of a BDSM community. So if Judge Horkins makes the ruling that Ghomeshi is guiltyon the grounds that Lucy Decoutere could not give Ghomeshi permission to choke her as part of sexual ‘play’, I would expect that ruling could be contested, simply because there are very likely members of the BDSM community who could make the legal argument that choking can be legally consentable; orgasm via temporary asphyxiation, for example.

In the former (1 – 4), While Henien seems to be going for a determination of on-going consent to ‘rough sex’, I suspect that she could fail, simply on points of law – no judge can fail to note lack of evidence of initial consent, implied or otherwise, permissible or otherwise, and because there is similar fact evidence that Henien has not successfully contested

As yet.

As I write this, Henein has begun trying to discredit the ‘similar fact’ evidence; complainant 3 and 2 have been shown to have shared their stories, as women, and victims often tend to do as a part of processing a trauma. But in the eyes of the law, that story-comparing leaves Henein scope for the argument that the 3 women colluded in their testimony, thus devaluing the strength of ‘similar facts’ evidence.

At this point, as I see it, it comes down to two things: Is Judge Horkins susceptible to Henein’s smoke and mirrors? and does Crown Attorney Gallagher have some Windex up his sleeve?

Some links very much worth reading:

re: Traumatic Memory & Sexual Assault

https://storify.com/empathywarrior/to-understand-the-ghomeshi-trial-we-also-need-to-u

http://nij.gov/multimedia/presenter/presenter-campbell/pages/presenter-campbell-transcript.aspx

http://time.com/3625414/rape-trauma-brain-memory/

http://www.cbc.ca/news/technology/trauma-brain-memory-neuroscience-1.3431059

Re: Giving testimony as a sexual assault complainant:

http://canadalandshow.com/article/when-your-friend-stand-ghomeshi-trial

re: Marie Henein

re: Whacking

http://www.winnipegfreepress.com/opinion/columnists/whacking-the-complainant-367563261.html

re: Canadian Criminal Code, and Consent to Harm

http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-46/page-63.html#docCont

“Refugees” Welcome, Canada?

There are so many types of “refugees” and many ways to describe them. We have used terms like Displaced Persons (“DPs”), Victims of War, Illegal Immigrants, Asylum Seekers, Émigrés; each label is polysemic, encoding semantic and political trajectories backwards and forwards in time. Compare the representation of Elsa, the heroine of Casablanca, as she bends legal and moral rules in order to escape Morocco under Nazi control, with representation of contemporary Khurds or Syrians as they flee the war front which has taken over their doorsteps. Or compare the representation of heroic Rick, who condones Elsa’s and Victor’s attempts to escape and conives with the shady Signor Ferrari, with contemporary human traffickers.

However labelled and represented, refugees are the subject of much professional expertise, policy, surveillance and document-anxiety. The United Nations has an entire bureaucratic directorate, a High Commission -the UNHCR- devoted to the fact that refugees exist. People who are called refugees (or DPs or illegal immigrants, etc.) are characterized by their nation of origin, by their sex, gender, religion, age, education, medical needs, income-potential, work experience; sometimes we characterize refugees by their experience with violence and/or hunger; sometimes we recognize a refugee by how long they have been in limbo, that physical and psychological state of deterritorrialization also known as a ‘refugee camp’; a place which itself might actually be a town in everything but official municipal policy and potential for its residents to plan a future for themselves.

No matter how it is described, being a refugee sucks. As poet Warsan Shire says, no one flees home unless “home is the mouth of a shark”.

In Canada these days, we are saying “Refugees Welcome” and congratulating ourselves on having Canada back. We say “refugees welcome” in sympathy with the middle-class seeming people currently fleeing the Syrian conflict, but also in opposition to what we see and hear from the bombastic rhetoric of American presidential candidate-wannabes; and we feel very good about ourselves.

But our much-lauded new government, while aiming to put a dent in the current disaster of asylum-seekers’ deaths and bring some 20,000 refugees to Canada, and in simultaneously seeking to defray racist fear-mongering about ‘extremist Muslims’, is prioritizing ‘safe refugees’ – those vetted by the UNHCR. So those receiving Canadian welcomes are privately sponsored, or coming from long-term, well-provided camps in Lebanon & Turkey. We are delayed in meeting our national target partly because those acceptable to Canada are themselves sometimes reluctant to relocate so far from their home terrains. They are not the people we see being rescued from boats in the Mediterranean, pressed against yet another border fence in Hungary, or rushing trucks heading into the Chunnel.

I bet some of the 3000+ people sinking and freezing in the French winter-mud of the Dunkirk suburb/fenced refugee camp of Grande Synthe (AKA ‘The Jungle’) or squatting in a refugee hell on Lesvos would be happy to accept a Canadian welcome.

We could meet our goal of 20,000 and more if we actually welcomed #refugees.

*Photo credit @Msf_Sea http://bit.ly/1Dwhxjc

Follow suggestion: Mohammed Ghannam @MohGhn, https://www.facebook.com/MSF.VoicesFromTheRoad/ (Jan 10, 2016).

50 major public research organisations in Europe adopt four new common principles on Open Access Publisher Services

JASON ANTROSIO’s 1st response to the Anthropology-Haters

Jason Antrosio, author of the Living Anthropologically blog, wrote a great response to the flurry of neo-liberal detractors who began declaring anthropology as a poor option for university students. As Jason points out: Anthropology may be the worst major if you want to become a corporate tool, but it is the best course of study if you want to help change the world for the better. Take a read. Even though written in 2012, it’s still very relevant. Then stroll over to Paul Stoller’s discussion of anthropology as a university major and critique of the rankings systems that think universities can be compared just like blenders. After that, I recommend reading Thomas Hylland Eriksen’s “Engaging Anthropology: The Case for a Public Presence” (Berg 2006/Bloomsbury 2012).

But begin with Antrosio’s bow shot across the neo-liberal ship of ‘education as merely pay-cheque preparation’.

http://www.livinganthropologically.com/2012/08/21/anthropology-is-the-worst/

Metrics: An Addendum on RAE / REF

We have had overwhelming support from a wide range of academics for our paper on why metrics are inappropriate for assessing research quality (200+ as of June 22nd). However, some have also posed interesting follow-up questions on the blog and by email which are worth addressing in more depth. These are more REF-specific on the whole and relate to the relationship between the flaws in the current system and the flaws in the proposed system. In my view the latter still greatly outweigh the former but it is useful to reflect on them both.

Current REF assessment processes are unaccountable and subjective; aren’t metrics a more transparent, public and objective way of assessing research?

The current REF involves, as the poser of the question pointed out, small groups of people deliberating behind closed doors and destroying all evidence of their deliberations. The point about the non-transparency and unaccountability…

View original post 2,002 more words

Sand in My Syllabus; Teaching Anthropology ‘Way Off Campus

In December 2012, I was invited to Oslo to give a presentation on pedagogy. This is what I said:

I’ve taught anthropology in university classrooms; a lot. Many have been multicultural, and multigenerational. I’ve also been privileged to teach anthropology in some unusual classroom settings, for example, on cruise ships, in academic studies abroad (KulturStudier; Tonga Field School), and in the traditional territory of the Nisga’a First Nation.

In the campus classroom and off-site, my teaching philosophy is influenced by Chickering’s and Gamson’s (1987) Seven Principles for Good Practice in Undergraduate Education:

- Encourage student-faculty contact

- Encourage cooperation among students

- Encourage active learning

- Give prompt feedback

- Emphasize time on task

- Communicate high expectations

- Respect diverse talents and ways of learning

While working as a Capacity Building Advisor, I was able to partake of a training programme called “Making a Difference” that focused on adult education and change management. Two of the key lessons were that

- people learn best when they are having fun, and

- they accept new ideas when those ideas have relevance for them.

I think you’ll agree with me that one of the chief goals of anthropology as a discipline is to encourage the valorization of diversity; or to put it another way, to counter stereotypes and stigmas about the ‘cultural other’; countering stereotypes is, obviously, introduction of a ‘new idea’ .

Traditionally, anthropologists have done our stereotype-countering with entertaining lectures and monographs, whereby the anthropologist’s experience stood as proxy for the student’s experience: the anthropologist went, learned, returned and represented the ‘other’ to an audience of learners. We still do that in our university teaching today. We use stories and writings to represent the cultural other to our students – whether they be in a university classroom or the deck of a cruise ship.

— Sometimes this works to counter stereotypes. Often, it does not —

Therefore, I turn to teaching games to help make lessons more memorable, and fun. Good teaching / learning games are like a ritual: they offer multiple, polysemic, lessons. Teaching games offer the chance to draw analogies from one instance or experience, to another (like any good metaphor). They also provide a kinaesthetic experience to augment the usual oral and aural ways that students are taught. My favourite is the Partnership Toss Game.

How to play Partnership Toss

A group of people stand in a circle; the circle should be at least 1.5 metres in diameter; more is fine, but not beyond 3 meters. One person tosses a small object (i.e.: a bean-bag) to another person, anywhere across the circle. That person tosses the object to a different person and so on, until everyone has received a toss of the bag and it eventually makes its way back to the original thrower. Then the group has to repeat the exact pattern of tosses – remembering who tossed to whom, in what order, over and over again. When the group has the pattern complete and begins to do it rapidly and automatically, the teacher/facilitator introduces a second bag; now the group has to repeat the pattern with two bags. then introduce a third bag. If things go well, and the pattern is maintained and rapid, the final step is to pull a thrower (any) out of the circle and see what happens. Usually, there is lots of laughter.

What does this game teach? Among other things, players spontaneously conclude that:

- Groups of people can learn and perform complex tasks,

- The outcome of the task depends on individual members doing something quite simple and limited

- Communication helps keep complex tasks and patterns flowing

- When routines become established, we don’t have to think, we can just act automatically

- That we can have fun when doing our part, take pleasure from a routine task done in partnership

- But there can be a limit to what the individuals in a group can do when asked to take on more of the same task

- Even the best-practised routine can fail if over-loaded, or if one member/segment of the system breaks down or is removed.

Overall, we can use this game to draw several analogies, for example, on the theme of “Partnership Makes Complexity Easier” –such as in a Polynesian or Melanesian or Tamil village; stereotypes about ‘simple’ village life do not represent the complexity of the system.

Penn State University has devised some diversity teaching games that I like to use, depending on the class level / background experience:

Five Moments

Give each participant a piece of paper. Have them write down the five moments in their lives that were most important for shaping who they are today. Go around and have each person share two or three events in their life. Facilitate a discussion on how the major events in life are universal and are not a respecter of people’s differences.Stereotype Wall

Place posters on the wall that have titles of different groups (such as ethnic groups, genders, sexual orientations and socioeconomic classes). Have people walk around the room and write something that they have heard about these people or a way in which this group of people is stereotyped. Facilitate a discussion on where these stereotypes came from and if they have veracity.Chain of Diversity

Pass out six slips of paper to every person. Have each person write down a similarity and a difference that they have concerning other people in the room on each slip of paper (for a total of six similarities and six differences). Have members share two of their strips. Then, using glue or a stapler, link all of the strips together in a chain that shows that, no matter how divided people may be by their differences, their similarities will always bring them together.

As you may be able to guess by now, I am a fan of experiential learning, creative classrooms and of the transformative power of the ethnographic experience. In my opinion, nothing teaches anthropology as well as learning by doing. I tried to do this myself with my ethnographic field school in Tonga.

Ethnography itself is undergoing a remarkable efflorescence, both outside anthropology and within. This is coupled with an increased interest in ethnographic training. Around 2005 – 2007, the US-based National Science Foundation [NSF] awarded several grants for training in ethnographic methods. The one I am reporting about here, is a particular ethnographic field school which is, to the best of my knowledge, unique.

Exactly how does this field school differ from most ethnographic field schools? Emphasis on participant observation, taught (in part) by observing participants:

The Ethnographic Field School; Tonga, was collaboratively designed with the residents of the village where the field school was to take place.

In the early stages of the project development, I travelled to Ha’ano, a village where I have had ongoing and deep relationships for over a dozen years. In village meetings, small group and individual meetings with village elders, and with members of the women’s development committees, we strategized about questions related to pedagogy and content: We asked ourselves, how and what to teach students who might become ethnographers in the future? I had my own ideas about criteria, but I wanted the hosts of the school, and the people usually relegated to the role of ‘observed’ and ‘interviewed’ to say what, and how, they wanted the students to learn.

We agreed that the underlying principles of the school should be as follows:

The ethnographic field school would provide an experientially rich entré to doing ethnography in the ‘classic’ sense.

The students should enjoy the experience.

The village and island residents should enjoy and benefit from the Field School.

The students would acquire respect for Tongan culture, society and people.

The students would appreciate the covenant of reciprocity and respect that underlies the long-term ethnographic encounter.

Building on these principles, we agreed that key elements of the Fieldschool would be:

Cultural orientation and lessons in social etiquette prior to staying in the village.

Classes on ethnographic ethics, mapping, kinship, participant observation, interviewing, visual and written field notes, Tongan culture, history, economy, politics, ecology, fishing, farming, textile-making, child-rearing, ceremony and language.

Classes in anthropology to be taught by academic professor, classes on Tongan ethnography to be taught by Tongans.

Tongan culture experts identified as potential interviewees or invited to teach in their areas of expertise to be paid or offered honoraria.

Students homestay in the village; one student per family; they participate in household chores as if a son or daughter of the household.

The Field School would reimburse the village, each homestay family, and provide tranlation assistance to students.

All ethnographic information recorded by students during the fieldschool to remain unpublished.

Based on those meetings, I drafted a field school proposal, and submitted it to the Study Abroad Program at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. When the proposal was accepted, and with financial support from the Centre for Pacific Islands Studies, I hired a particularly skilled and well-respected Tongan woman as Field School Assistant, to help make arrangements, coordinate travel, translate documents, and act as curriculum development partner.

Thus, from the outset, the fieldschool was participatory, culturally-sensitive in design and action-research oriented.

While the students learned to be participant observers, the villagers learned to be observant participants in the training of ethnographers. In essence, people most used to being the subjects of research were recruited as active educators of a future crop of anthropologists:

In addition to acting as home-stay hosts, village residents were active teaching partners, providing

- guest lectures in the classroom,

- hands-on lessons in the gardens, reef, fishing boats and weaving houses, and

- ethnographic interviews on subjects negotiated between student, villager and instructor.

Perhaps most significantly, the villagers acted as evaluators of the students’ performance, contributing to the students’ final grades.

The most radical differences between my Ethnographic Fieldschool: Tonga and other forms of field school training lay in the privileging of local needs, and repositioning of knowledge, pedagogy, curriculum content, and authority to teach to those who are normally constructed as interlocutors rather than instructors.

The fieldschool offered fun, information, but also the praxis of subverting usual forms of power coded into the researched-researcher relation. I am very proud of this model.

Unfortunately, not all students can participate in a multiweek long ethnographic field school. However, even a short visit — like the one I did recently for KulturStudier in Pondicherry India — can be very important.

Last month, at my request, the Kulturstudier India team organized a field visit to a village (We tried to organize three day-trips; two went awry through no fault of the team, but the third, was accomplished very well). Special mention must be made here for Senthil Raja, Kavitha Ramkumar and Marie Nyhuus, who did a lot of the ground work, including running all around Pondicherry, drawing on personal connections, and giving lots of hours on top of their usual tasks; to Laurie Schmidt also, for endorsing the concept.

The main goals were to

1. Give the students a chance to experience actively the village they’d been viewing passively through bus windows.

2. Give the students a real life example that they could use to reflect upon when reading or discussing written materials to do with governance, gender, village life, education and/or the presence of religion in everyday life.

3. Test the opportunity to institute a regular village visit into the Religion and Power program.

In the last week of the anthropology lectures, the anthropology students walked from the study centre at Kailash Resort to Pooranankuppam, Pondicherry – புதுச்சேரி – in Tamil Nadu, India.

We met with the Vice-president of the village panchayat (an elected official at the local government level). He escorted us through the village, on foot, introducing us to some other members of the village leadership, and showing us some of the significant sites within the village – including the public gathering / performance space, the government school, the market, the government food-distribution store, and the central temple. We had great fun seeing inside the elementary school, and performed an impromptu song for the students in one classroom; we exchanged gifts, and had a question & answer session with two members of the panchayat. After 2.5 hours, we went back to Kailash for lunch.

While not exactly an ethnographic field school, it was an important learning opportunity. How for example, does it fit within Chickering’s and Gamson’s 7 principles?

- A field trip is a form of active learning; It makes discussions of village leadership more relevant because students have a context, they can remember, not imagine, the village leaders they met.

- Students were able to ask questions –of the local experts- and receive an prompt feedback. They didn’t have to remember to look it up later.

- The visit was structured in time, and space, so students knew to pay attention now, to stay on task.

- In terms of respecting diverse talents and ways of learning, experiential, learners had the opportunity to touch and smell, as well as see & hear; it was kinaesthetic as well as oral & aural.

- That particular walking visit didn’t go beyond the student-faculty contact that already existed, but it did put that contact in a different context. Insofar as the visit modelled ethnographic interviewing for students, it added value to the student-faculty contact.

- It didn’t go beyond student cooperation that already existed (but it could do, if properly structured).

- Expectations were communicated in terms of socially appropriate dress code; students were asked to prepare questions in advance. Whether these are ‘high’ or just ‘normal’ expectations is open to discussion.

How does it fit the 2 pearls criteria?

- In post-program evaluations, 53% of the students rated the visit as “very good”

- 33% said it was good.

- No one said it was poor or very poor.

Anecdotally, immediately after the visit, students reported a better understanding of what a panchayat is, how it works, and a better impression of the way local governance works in Pondicherry.

So: a small start, but an overall success.