Originally posted 20 December, 2020 by Arts Squared. Since first published, the University of Alberta’s General Faculties Council rejected the ‘Executive Dean’. However the position was still created, just with the title “Interim College Dean”. The “interim” part of the job title fell into disuse in about one week.

This was not intended to be an essay, not even a blog post. This began as a set of briefing notes collated for colleagues at the University of Alberta, prior to the now historic General Faculties Council meeting of 7 December 2020. That was the meeting where the university’s statutory and PSLA–mandated body was to consider the Provost’s proposal for academic restructuring, a proposal that included bundling faculties into “Colleges” and the creation of a new academic administrator position, that of “Executive Deans” who would lead the Colleges. In the days prior to the GFC meeting, the idea that the university might create Executive Deans was highly controversial. The role of an Executive Dean, as proposed by the Provost, would be to drive cost savings, and manage the shared administrative and fiscal aspects of the Colleges, while each faculty’s Academic Dean would manage their Faculty’s research and teaching affairs. Many members of the UAlberta community, academics, administrators and support staff alike, had reservations about the proposal for Executive Deans, but did not seem to understand what was driving this particular model for the restructure and cost-savings. These notes were my attempt to understand where the Provost’s idea of Executive Deans was coming from, and how the restructuring model was understood by those promoting it. They were also my attempt to draw on feedback from colleagues elsewhere who have experienced similar restructurings, similar governmental agendas for restructuring (austerity, reduction of public sector services), and similar, if not exactly the same, consultancy firms (i.e., the NOUS Group and McKinsey & Company). As an anthropologist, where the research goal prioritizes understanding “the other,” my approach was to begin by looking the horse in the mouth, so to speak. To do this, I read NOUS and McKinsey & Co.’s advisory and promotional materials, especially those referring to universities. That led me to read about McKinsey & Co. in greater detail.

Executive Deans: Understanding the “transformation” and “organizational effectiveness” backdrop

Much of the rhetoric that we have been hearing at the University of Alberta is that the university needs urgent “fundamental systemic reform,” in order to achieve the “organizational effectiveness” necessary to drive dramatic cost savings, while also “setting a bold new direction for the university of tomorrow” (see “U of A for Tomorrow”). Fundamental organizational transformation is a dramatic agenda, and UAlberta’s administration has contracted the NOUS Group to guide and manage the transformation process. The NOUS Group have a close relationship to global management consulting giant, McKinsey & Company. NOUS Group founder Tim Orton was a consultant with McKinsey & Co, and several others of the NOUS Group’s leadership came there from McKinsey & Co. (for example, directors Karen Lenane and Nikita Weickhardt, principal Gregg Joffe, and consultant Jack Marozzi appear in an easy Google search). Much of what we at UAlberta see and hear about restructuring can be traced to advice from McKinsey & Co.

McKinsey & Co. recognize that large scale organizational transformation fails about seventy percent of the time. They advise that universities often fail to transform because university leaders fail to hold the course. In their view, while university leaders may be “gifted educators, researchers, fundraisers, and academics,” they

“have little experience leading the transformation of a large, complex enterprise. Complicating matters, stakeholders often cling to deep sentiments about their institutions and their school traditions, which impedes change. And the shared governance structures at most universities makes it even more difficult to act quickly and decisively. When leaders encounter inevitable resistance, it’s not surprising that they often relent, and the project stalls, is abandoned, or becomes mired in a long implementation with poor results”. (See McKinsey, “Transformation 101.”)

In this perspective, Executive Deans are considered efficient because they evince —on paper— the “clear chain of command” that any general would appreciate. They make an organizational chart look neat and tidy. Business people speak of this “chain of command” as a way of assuring accountability. McKinsey & Co. have recommendations for “managerial spans of control” (number of direct reports) based on archetypes of managerial roles and work complexity—by time, standardization, variety, and skills needed. At the University of Alberta we are familiar with this type of task accounting in the form of the Hay points currently used to determine the ranks and salaries of administrative staff. More recently, we have been hearing about benchmarking data being provided to a company called UniForum, which UAlberta has contracted to help drive administrative restructuring and ‘savings of scale’ by reducing duplication of tasks across multiple units.

According to McKinsey & Co. the typical number of direct reports for a corporate Vice-President is three to five, and for the role beneath the V-P, six to seven. So when the Provost speaks of a scenario with a linear chain of command consisting of three Executive Deans and three Faculty Deans as his direct reports, it seems he is revealing the influence of McKinsey’s organizational thinking on his idea of the ‘right number’ of Faculties.

McKinsey & Co. claim that “rightsizing” —i.e., changing the type of manager or spans of control— “can eliminate subsize teams, help to break down silos, increase information flow, and reduce duplication of work …. [It will also] decrease the amount of micromanagement in the organization, [and create] more autonomy, faster decision making, and more professional development for team members.”

The promise is that for UAlberta, “rightsizing” will, in addition to cost savings, offer a pathway to “nimbleness” and “interdisciplinarity,” and may be good for career growth and job satisfaction. However, is rightsizing the right process for UAlberta? And at what cost?

Executive Deans: Understanding the structural pushes and challenges

The same McKinsey article that recognizes that large scale transformation tends to fail most of the time and that university leaders have a tendency to resist such transformation out of preference for things like collegial governance, also advises that “[a] key finding of our work is that while a reasonable degree of cost management is usually necessary, it’s more important to focus on improving student outcomes and identifying new ways to diversify and grow revenues” (emphasis added). We, in the opening salvos of restructuring at UAlberta have heard little about ways to diversify or grow revenues. Frankly, in the Canadian public universities system, “growing revenues” has limited options. Our post-secondary education system was designed to benefit the public, not generate profits within the universities themselves. The profits are accrued to society, with a better educated populace who, in knowing how to think critically and analytically, are better at self-governing, bring intelligence and reflection to their roles, earn better salaries, pay more taxes, and engage more civilly. The appeal of a company like McKinsey & Co. to a government seeking to reduce spending on universities lies in its provision of “strategies . . . that can help universities reduce their dependence on the typical two largest sources of revenue —tuition and government grants.”

Ironically, while McKinsey & Co. advocate a fairly shallow organizational hierarchy with a decreased distance from senior leaders to the front line, the organizational structure they promote actually creates a bimodal hierarchy that separates the senior leadership from those who actually produce value (the professoriate), by eliminating the middle managers (Associate Deans, for example). This leaves the highest echelon free to dictate decisions (or “be nimble”) and, coincidentally, to amass the bulk of an organization’s remuneration. This form of bimodal hierarchy, and McKinsey & Co.’s position in promoting it, has recently been blamed for destroying the middle class of North America (Markovits, 2020).

The Executive Dean model involves a structural hierarchy where authority derives from the top. Loyalty is therefore necessarily aligned with the Provost, President and Board of Governors, not, expressly, with the professoriate, nor even the students of the Colleges the Executive Deans would lead. This hierarchy is expressly anti-collegial in its governance model. Anyone who has studied chiefly social systems knows that good chiefs are those who recognize their dependence on their people, and who actively redistribute wealth. But with too much hierarchy, distance from the base, limited numbers of people with direct access to the “chief” and few with similar rank or authority (i.e., with no “middle”) comes more autocratic control. In UAlberta’s case, that greater autocratic control will come from the Provost’s office. Leadership will become more top-down, even less democratic, less a cohort of peers. In other words, corporatized.

When coupled with performance-based funding and key performance indicators (“KPIs”), we end up with no investment on the part of the senior leadership to resist the corporatized direction, and leaders who prefer to think of themselves not as academics but as CEOs. With Executive Deans we would see an expansion of the senior administrative leadership. Examples from other locales demonstrate actually this mode gainsays the goals of cost-saving and organizational effectiveness UAlberta is purportedly seeking.

I am quoting here from a recent research report on British and Australian senior leadership salaries:

The shift in the UK and Australian universities from collegial to more corporate forms of operating has engendered a corresponding shift in governance from stewardship to the agency. Professional management functions have come to the fore in the pursuit of business objectives and VCs [Vice Chancellors or the equivalent of university Presidents in Canada] both see themselves and are seen by others, including governments and government agencies, as chief executive officers. A significant uptick in V-Cs’ remuneration has occurred relative to other academic salaries. Market-based salary setting mechanisms, such as benchmarking, appear to drive these increases. (Boden and Rowlands, 2020)

See a synopsis of Boden and Rowlands’ argument in The Conversation, Australia.

The Australian and United Kingdom Experience

According to one Aussie colleague, “In Australia, the executive academics (Heads of department and up) do not teach and have no research expectations. They are contracted on a bonus based system. There is zero transparency about remuneration: nobody knows what anybody’s agreement is and there are many backdoor deals done” (Name withheld for confidentiality). My Aussie colleague describes this as another way of undermining any collegiality.

With Executive Deans, in fact all of the senior leadership, unless the executives’ performance indicators and budget structures are carefully wrought, there is little in the way of structural mechanisms to keep Executive Deans from becoming more like Provosts, less like colleagues, not even Deputy Provosts or Associate VPs. Boden and Rowlands (2020) recommend “maximum fixed ratios between vice-chancellors’ remuneration and average academic salaries.” But who in the UAlberta structure would or could make that happen? The Provost? Not the Executive Deans. It is doubtful that even this Board of Governors, despite their concern with austerity, would adopt that remuneration model.

Following from the McKinsey & Co. material on Chief Transformation Officers, and the experience of academic restructuring in Australia and the UK, Executive Dean positions will be filled by executives who have ceased to be primus inter pares (first among equals) and have become, rather like university presidents in Canada are now, former academics who behave like corporate CEOs. With that, there is great risk that Executive Deans will became more and more expensive.

The expense of Executive Deans will not necessarily be because they are great managers for their institution, colleagues, and students. Research from the UK has demonstrated that managerial efficiency fails as a determinant of Vice-Chancellors’ remuneration. Factors like student participation and research grants success don’t explain the remuneration increases either. See Bachan and Reilly, 2015. Surprise, surprise, age, size, and reputation of the institution are more reliable predictors of V-C pay. See Virmani, 2020.

With performance measures that focus on annual rankings and corporate fund-raising rather than faculty, staff and student satisfaction, you end up with a cohort of executives whose career path is not based on growing within a university community to which they are dedicated. Instead, these senior academic administrators flit from one university to another, increasing their remuneration as they move up the ladder in terms of institution reputation and size. (That’s one way to understand the imperative to “be nimble.”)

The Outlook for University of Alberta for Tomorrow

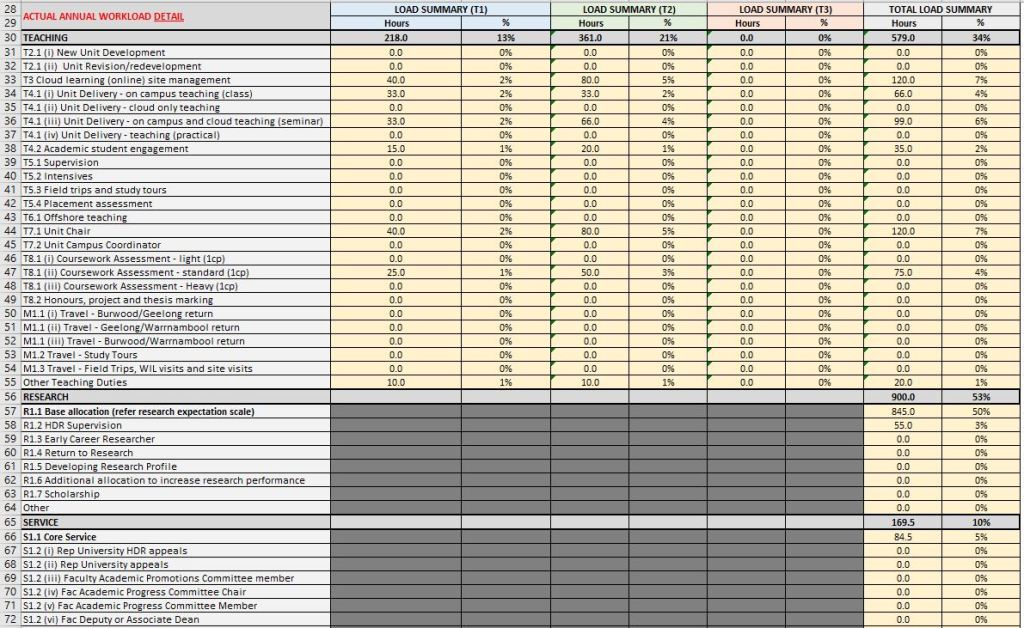

Whence will come the cost savings UAlberta needs? They’ll come from draconian measures, such as vertical cuts, but beginning with cuts of academic teaching and support staff positions, and downward pressure on the professoriate via managerial mechanisms such as the Faculty Evaluation Committees, algorithms that determine academic performance, and Key Performance Indicators. A colleague shared a real prof’s workload evaluation spreadsheet, from a major Australian university. I’ve redacted the name.

My colleague sent the Australian prof’s workload summary with this note:

Hi Heather,

This was provided by a colleague. Read and weep.

Note in the research tab how different research publications are weighted as “points”. A minimum number of points must be achieved each year or the algorithm under the teaching calculation is changed to ensure additional teaching hours are performed. So for an ordinary senior lecturer (not a prof) to keep your research allocation at 40% (a typical 40-40-20 workload distribution) you would need to produce 7 research points a year – that is 7 book chapters, or 1 book and 2 chapters, and so on. A prof would be expected to achieve 11 points – so two books and a book chapter. Obviously none of this is sustainable if even possible. So the effect is that everybody does a LOT of teaching (70-10-20)…

This is what is really meant by “performance-based” universities.

Cheers

[name withheld]

Buzzwords Decoded

It is unfortunate that two wonderful concepts—nimbleness and interdisciplinary— have been captured by the Provostial rhetoric and transformed into buzzwords.

“Nimbleness” is code for the freedom to expand the precariate and make vertical cuts.

“Interdisciplinarity” is code for merging departments.

Recently, those of us observing the UAlberta’s Board of Governors’ meeting on 11 December 2020 were offered another buzzword to consider: “Laser focus.” This is less difficult to interpret. Laser focus is code for relentless inflexibility, autocracy, and hatchet-wielding, all in the name of KPIs. Actions associated with laser focus include denying collegial governance, breaking collective agreements, pitting departments and colleagues against each other, creating chilly workplaces, and hailing the hatchet-wielding executives with titles such as “Chief Transformation Officer.”

The McKinsey Touch

Look soon to see McKinsey-inspired expansion of the mandates for the Board of Governors.

For more background on McKinsey & Co. I recommend Duff McDonald’s The Firm (2014), and investigative journalism in The New York Times and The Independent.

After learning all this, I have one or two questions more. Why is it that management consulting firms only offer universities one model for organizational effectiveness, leadership, and transformation, a model based on a capitalist corporation? Instead of accepting a huge failure rate in transformations, why not offer universities an organizational structure more similar to what a university is? Yes, our university has to change. But does it need to be corporatized? Why aren’t our current leaders demanding —of themselves— expertise, higher degrees, MBAs even, in co-operative management? Why are they not demanding of the consultants they hire —NOUS, McKinsey— something that respects the collegial governance system and its longue durée of successful production and sharing of innovation, creativity, critical thinking, and knowledge?

The answer to these questions may lie far from the Alberta prairies, at Harvard’s Business School.

Finally, for more on McKinsey & Co, listen here: