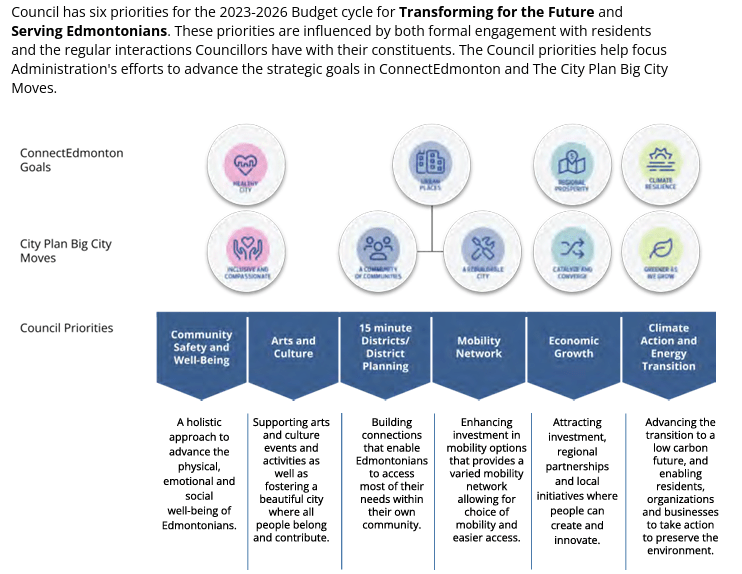

I wrote this first in 2023 as a thread of tweets, back when Twitter was good and Edmonton’s city council had failed to fully budget for completion of the planned bicycle-as-transportation infrastructure. Mine was an audacious, madcap response to council budgeting just 50% of the estimated cost for a city-wide sytem of connected routes for active transportation, understood at the time to be bike lanes, aka mobility lanes. in a $7.9 billion dollar capital budget that allocated $600 million for “Recreation and Cultural Programming”, and $517.6 million for “Yellowhead Trail Freeway Conversion”, only $100M for enabling Edmontonians city-wide to choose to bike, walk, or roll instead of drive. This, despite a single car overpass costing $180m, whilst three of six city priorities for the 2023-2026 budget and an overall city goal for 50% of all trips to be made “using less carbon intense modes like cycling, wallking and transit”, depended on the modal shift that a connected, safe, active transportation network would provide.

I’m updating the original blog post now, in October of 2025, just after municipal elections in which we saw unprecidented intrusion by the provincial government into municipal affairs (eg: here, and here), thousands of political dollars donated to a new party hoping to ensure UCP aligned candidates were elected, and candidates who tried to cancel bike lanes and then used bike lanes as a dogwhistle to rally support to a regressive agenda. Despite the anti-bike, anti-15 Minute city, anti-infill rhetoric, political polling did not indicate bike lanes were actually an election issue. A Taproot poll early in the campaign cycle indicated that Edmontonians want a more walkable city, including ease of movement for all-season cylists and mobility-device users:

“For non-drivers, crossings are brutal for weeks on end,” a respondent said. “Bikers, without bike lanes, are left with few options beyond the sidewalks, but then are forced to make dangerous road crossings, as well, through four-to-six inches of mush. (I can’t imagine what the experience is like for people who use mobility devices).” (Gallant, The Pulse, Sept 25’25)

In the end, the majority of councillors elected or re-elected were those who support active transportation, 15 Minute city planning, densification and using municipal power to ensure well-being and housing for unhoused Edmontonians.

We even elected an all-season-cyclist as mayor!

That 2023-2026 Capital Budget that seemed so progressive will soon end. Planning for the next budget cycle (2027-2030) will likely start as soon as the new councillors are sworn in. It is therefore not too early to consider these questions:

- Did we get the active transportation network that would allow for the city-wide, all-season, bicycle-as-transportation infrastructure that we needed?

- What did the original $100M cover, and what still needs to be completed?

- Will access to active transportation be equitable, so that all neighbourhoods have safe, accessible routes to ride to retail, schools, entertainment, etc.?

- What do the residents outside the Henday (Edmonton’s ring highway system) need, so as to be able to choose bikes as transportation?

- Have we, as a city, reduced our carbon footprint?

- Are we going to meet our transition to low-carbon goals?

However those questions are answered, it’s pretty clear that wider circumstances –USA’s rogue attitude towards trade deals, persistence of the homelessness and opiod poisoning crises, intransigence of the provincial government– mean that money will be tight for 2026-2030. The next capital budget cycle will not be easy.There are many of our neighbours who bought the koolaid that active transportation and walkability are frivolous. Which means that perhaps a novel idea for policy that considers a new source of revenue, that incentivizes a greener, bicycle-savouring, property tax-stabilized municipal budget is not so madcap after all?

—————— ~~~~——————

Ok, bear with me; working through an idea.

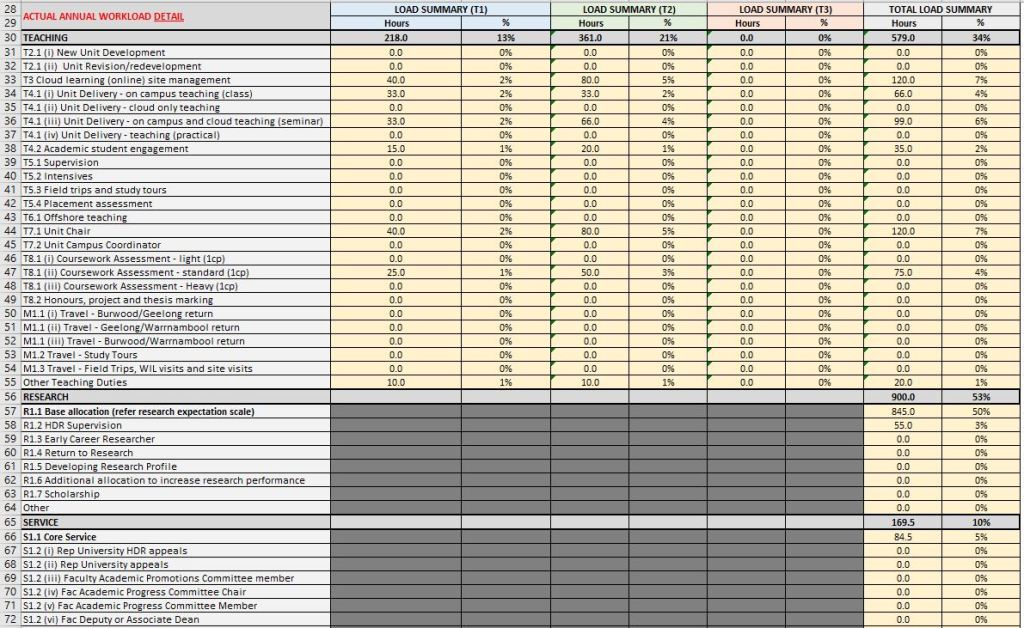

The City of Edmonton’s urban and budgeting planners have estimated that to institute the bike transportation infrastructure needed to meet the city’s climate crisis, human well-being & municipal tax-affordability goals, would cost $200M (in 2022 dollars; make that $225 million in 2026?). It’s a very low price compared to other transportation infrastructure costs in the city’s budget.

But in the budget deliberations, only $100M was allocated for the 2023-2026 fiscal years.

So we have a shortfall of $100M over the 2023-2026 budget cycle (call it $120M for 2026).

Funding bike-transportation infrastructure is a smart move on city council’s part.

Car-dedicated infrastructure (roads, parking, parking lots, road maintenance machinery, etc.) is a huge part of a municipal budget, and no matter how much is budgeted, it is always inadequate: cities have learned that building roads induces demand for more traffic. It increases costs, risk, noise, and pollution rather than easing congestion or generating revenue. Car-infrastructure is ruinous for city budgets. Car-infrastructure is a disincentive to climate change mitigation. Car-infrastructure makes urban areas unpleasant. Taxpayers are never satisfied with what cities and municipal councils institute.

Bicycle infrastructure by contrast is cheaper to maintain. Bicycles don’t beat up the roads the way cars and trucks do. Bicycles don’t kick up particulates or create din the way cars do. Bicycle riders have better range of vision, fewer blind spots, than drivers, and they move at a slower speed, thus reducing collisions and dramatically reducing injuries and deaths. With bike transportation infrastructure, induced demand actually reduces risk, noise, pollution and costs to municipal budgets, and thereby to taxpayers.

So, it’s in a city budget maker’s best interest to encourage the increase of bicycle use while incentivizing decreases in car use. But funding 50% is like riding half a bicycle. Doable, not optimal. What are a city’s options?

In Canada, municipal legislation gives cities property taxes, bylaws & zoning as their tools. Fairly limited options. Municipalities may not, for example, impose extra taxes on drivers using certain neighbourhoods, the way UK & EU cities have done to reduce cars & incentivize public transit or bike use. Sadly, Canadian municipalities don’t have the lever that NYC does to reduce congestion and raise revenues.

But, WHAT IF the city used the prerogative over property taxation to assess a special “Climate Crisis Levy” on commercial properties dedicated to activities that enable car-use? WHAT IF the city dedicated all revenues from that extra levy to meeting the $100M-plus shortfall?

Commercial properties, not residential properties. What kind of commercial properties? Low-hanging fruit are properties hosting gas stations, car dealerships, automotive repairs, auto-body shops, tire-sellers, vanity mufflers, car-washes, etc.

Of course, the property owners (landlords) would kvetch. Then they would pass on the levy-cost to the commercial operators leasing those properties. They, of course would raise their prices to their clientele, the citizens engaging in transportation choices that favour car-use, negatively impacting our environment, local quality of life, and collective municipal costs.

While building the piggy bank for the climate crisis-fighting infrastructure we need, ie: the missing $100+ million, the increased prices for car-fuel, car-repairs, etc, would create disincentive pressure on car use, whilst simultaneously ensuring the car-users pay (indirectly) for the costs they impose on the municipal budget.

City council could vote to make such a special assessment temporary – eg, until the bike network/active transportation infrastructure project is completed & paid for. That’s how the province of British Columbia funded the Vancouver Airport upgrade- through a temporary levy on every traveller transiting YVR. Or council might not. City council might, for example, use the levy to pay for a bike network, then dedicate any surplus to neighbourhood renewal, community gardens, parks, e-bike subsidies, free bikes for refugees, bike-taxis for seniors’ residences, or any other climate crisis mitigation and improved urbanism measures they choose.

Would a city like Edmonton do this? Councillor Aaron Paquette generously responded to my original tweet thread and pointed out that while this mechanism would work IF a city was isolated, municipalities are not isolates and may be competing with neighbouring municipalities for commercial land rents. Municipalities are therefore leery of chasing away property tax paying commerce. However, I pointed out, in the middle term, it is unlikely businesses like gas stations or tire warehouses will accept the major expense of relocating their business across municipal boundaries – their customers are local, and the requirements for environmental cleanup after quitting a site are costly and complicated. It’s a better business decision to just pass on the cost. If, over the long term, those businesses decided to change their business model, shift away from serving car-users, or if property owners become more reluctant to lease their land to car-serving business, that’s actually a positive for the city, which should prefer urban commerce which enhances a net-zero, circular economy.

Would the ‘municipal isolation’ concern be a problem, really? Wouldn’t other municipalities see the benefit of such a mechanism too? Wouldn’t this be an opportunity for mayor-to-mayor leadership and solidarity? Yes. But as Councillor Paquette points out, the Province might intervene, and this intervention could be counter-productive. This has happened in Alberta; we’re expecting more of it. On the other hand, municipal mayors have stood in solidarity and cooperated in lobbying and negotiations with provincial authorities in other circumstances. It could happen again. As Anne Hidalgo demonstrated, a mayor can be threatened by the powerful, and she can stand “on the right side of the story”, and be vindicated by posterity.

What I like about this kind of solution is that it works subtly, to reduce the unrecognized subsidies municipal residents pay for drivers’ use of our tax-payer property-tax funded infrastructure, while funding the transition of our urban space without raising residential property taxes (making street parking un-free is a good idea too). It’s a polluter-pay mechanism, in which the ‘perverse incentive’ is one from which residents and the environment benefit, in the short-term as well as the long-term.

It would require a courageous, committed council, ready to incur the kvetchers’ temporary wrath. And let’s be clear -commercial property landlords are political campaign donors (if we didn’t know it in 2023, we certainly saw it in 2025). So yes, they have some influence. But their influence did not carry the 2025 election. So perhaps we have a window here, in the 2026-2030 budget cycle. It would also require visionary leaders, willing to work with their counterparts in other municipal and provincial offices, and with businesses to be impacted. Some of those businesses might decide to change their business model –gas stations for example could again serve bicycle users (that’s probably inevitable)– all for the greater good.

Councillor Paquette pointed out (in 2023) that there was (and I think, is even more, now), commitment on council. For example, they supported a motion from Councillor Salvador for an environmental fund. Paquette also opines that change occurs at the pace the electorate is comfortable with, no faster. Probably so. But I think we’ve seen in the 2025 election that electors will shift their thinking and their behaviours, as they hear new ideas, and experience new opportunities. Our new mayor, Andrew Knack, was not a bicycle commuter when he first was elected. To his credit, he accepted an invitation from some bike commuters, who showed him what cycling in the city was like, and he changed his view! Parisian mayor Anne Hidalgo demonstrated that social change –modal shift– is possible when she pushed for a dramatic shift to bike lanes for Paris. Research by urbanists and transportation engineers show transition from motornormative, car-default urban-infrastructure can be swift, where people speak up, and political authorities risk bold decisions. Amsterdam is the obvious example. But Oulu, in northern Finland, might be a better comparator for Edmonton. In Oulu, political decisions led to an extensive bike-transportation network of routes that are maintained all seasons, making Oulu the winterbiking capital of the world. That is, perhaps a better example for a city with one quarter of the year where snow and ice can impact cycling. Although, with climate change, Edmonton winters are seeming damper, so perhaps Copenhagen would be an example to emulate.

I don’t really think Edmonton’s council would ever create such a levy. The point is, Edmonton’s city councillors have a mandate to be more all-season, all-riders, all neighbourhoods, bicycle-as-transportation-friendly. So let’s make Edmonton the Amsterdam-Copenhagen-Oulu-Paris of Canada.

the local pharmacist and use it to sooth her cranky infant. A mother of Cree, Mohawk or Anishnaabe ancestry who made a tisane including dill or fennel, sugar, baking soda, and watered gin could be accused of providing alcohol to a minor, be declared unfit as a parent, and have her child removed. Yet commercial preparations of gripe water had an alcohol content ranging from 3.6% to as high as 9%, even into the early 1980s (

the local pharmacist and use it to sooth her cranky infant. A mother of Cree, Mohawk or Anishnaabe ancestry who made a tisane including dill or fennel, sugar, baking soda, and watered gin could be accused of providing alcohol to a minor, be declared unfit as a parent, and have her child removed. Yet commercial preparations of gripe water had an alcohol content ranging from 3.6% to as high as 9%, even into the early 1980s ( The Lost Jingle Dress is my first ‘published’ piece of creative nonfiction. The story lauds the small, tight-knit community of Jasper, Alberta. I wrote it in 2014, and it was performed by Stuart McLean in 2016 for the CBC Radio program Vinyl Café. It aired in the story exchange segment of the “Indigenous Music” episode of June 3 & 4, 2016.

The Lost Jingle Dress is my first ‘published’ piece of creative nonfiction. The story lauds the small, tight-knit community of Jasper, Alberta. I wrote it in 2014, and it was performed by Stuart McLean in 2016 for the CBC Radio program Vinyl Café. It aired in the story exchange segment of the “Indigenous Music” episode of June 3 & 4, 2016.